Alfred Nobel’s life ended quietly on December 10, 1896, in the gentle warmth of the Italian Riviera, but the irony of his final years is that almost nothing about his legacy would remain quiet. His death at age sixty-three marked the beginning of one of the most profound transformations in modern intellectual and scientific history. The man whose name had long been associated with the raw power of explosives would, through one stunning and unexpected twist, become forever linked to the advancement of knowledge, human progress, and international peace. What began as a life centered around invention—particularly inventions that wielded fearsome power—ended as a legacy devoted entirely to rewarding humanity’s greatest achievements.

Alfred Nobel was born on October 21, 1833, in Stockholm, into a household that could best be described as intellectually restless. His father, Immanuel Nobel, was an engineer, an inventor, and something of a relentless dreamer whose fortunes rose and fell as fast as the markets he chased. When Alfred was still a child, Immanuel moved the family to St. Petersburg, Russia, where he secured work as an engineer for the Imperial Army. It was in Russia, surrounded by the machinery of war and industry, that Alfred’s natural abilities began to take shape. He developed a fascination with chemistry and engineering, two disciplines that would determine the arc of his life.

By the time he reached adulthood, Alfred Nobel was well on his way to becoming one of the most prolific inventors in Europe. He studied in Paris and worked in factories and laboratories across the continent. His sharp mind and unusual intuitive sense for the behavior of chemical compounds allowed him to see possibilities where others saw only risk. By 1863, he had developed a usable form of nitroglycerin—far more powerful than anything previously available for blasting rock or excavating tunnels. But nitroglycerin was dangerously unstable, often exploding unpredictably, killing workers and damaging equipment.

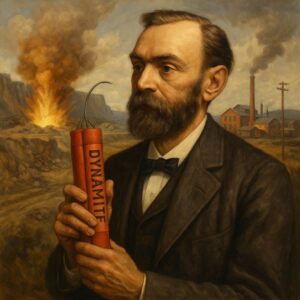

The turning point came in 1866, when Nobel discovered that combining nitroglycerin with silica and diatomaceous earth created a clay-like mixture that was both powerful and stable. He named it dynamite. With dynamite, construction firms could blast through mountains, carve railways through continents, and accelerate the industrial age into a new chapter. Nobel patented the invention, founded factories across the world, and rapidly became one of the wealthiest men of his generation.

But dynamite brought something else—controversy. Many saw it as a tool for progress, yet others saw it as an instrument of destruction. Nobel, who was intensely private and somewhat emotionally distant, carried these criticisms quietly, perhaps even painfully. In his personal life, he suffered profound loneliness and loss. His first and only love, the Austrian pacifist Bertha von Suttner, became a lifelong correspondent rather than a partner. His younger brother Ludvig died in 1888. And then came the incident that changed everything: a French newspaper mistakenly published Alfred Nobel’s obituary—believing that it was he, not his brother, who had died.

The headline read: “The merchant of death is dead.”

The article went further, condemning Nobel for becoming rich by inventing a substance that killed people more efficiently than ever before. Imagine the shock of reading your own legacy reduced to such brutal clarity. Nobel, deeply shaken, realized that this might truly be how history remembered him. And in that moment of painful introspection, a new idea began to take shape—one that would eventually redefine the meaning of his name.

By 1895, Nobel had quietly drafted a will that stunned even those closest to him. He left nearly all of his vast fortune—equivalent today to billions of dollars—to establish five annual prizes. These prizes would be awarded to those who had conferred “the greatest benefit to humankind” in physics, chemistry, medicine, literature, and peace. He did not consult his family. He did not request approval. He simply wrote the instructions, sealed the document, and ensured that his wealth would build a legacy far different from the one his inventions might have suggested.

When the will was read aloud in Stockholm in January 1897, Sweden erupted in debate. The will was legally unusual and politically delicate. Some argued that Nobel’s estate should rightfully go to his relatives. Others objected to the international nature of the prize committees. Even the Swedish King expressed disapproval. Yet Nobel’s wishes ultimately prevailed, as if the moral momentum behind his vision could not be denied.

On December 10, 1901—five years to the day after Nobel’s death—the first Nobel Prizes were awarded. The ceremony marked an extraordinary moment, not just for science and literature, but for a world beginning to recognize that human achievement extended far beyond national boundaries. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen received the physics prize for discovering X-rays, a breakthrough that revolutionized medicine. Marie Curie, who had inspired Nobel’s admiration during his lifetime, received her first Nobel just two years later. The literature prize went to Sully Prudhomme, while the peace prize was awarded to Henry Dunant and Frédéric Passy, two pioneers of humanitarian thought.

The world immediately understood that something monumental had begun.

In the decades that followed, the Nobel Prizes became the global gold standard for intellectual accomplishment. Scientists whose work changed the course of history—Einstein, Bohr, Watson and Crick, Fleming—walked across the stage in Stockholm to receive an award made possible by the man who once feared being remembered only for creating explosives. Writers who reshaped the world’s imagination, leaders who fought oppression, doctors who cured diseases—all came to stand under the banner of Nobel’s vision.

The irony, of course, is profound. A man who built his fortune on controlled destruction ultimately engineered one of the most constructive philanthropic legacies ever conceived. Nobel never married, never had children, and lived much of his life in isolation. But he left behind an idea greater than any invention: the belief that humanity’s brightest minds should be honored and encouraged, that progress was something worth investing in, and that peace—fragile though it may be—deserved recognition equal to any scientific breakthrough.

Today, the Nobel Foundation’s endowment has grown to billions, allowing the prizes to continue indefinitely. More than 600 laureates have been honored, some of them twice. The awards have shaped careers, influenced political movements, and propelled scientific revolutions. They have sparked debate, controversy, admiration, and sometimes outrage—but always engagement. The world watches each year, waiting to see who has nudged humanity forward.

In a very real sense, Alfred Nobel succeeded in rewriting his own obituary. He ensured that he would be remembered not as the merchant of death, but as the architect of one of humanity’s greatest traditions—one that celebrates imagination, discovery, and the pursuit of peace. His life reminds us that redemption is possible, that legacy is malleable, and that a single moment of clarity can alter the destiny of millions.

When we speak his name today, we think not of dynamite but of brilliance. Not of destruction but of progress. Not of explosions but of enlightenment.

And perhaps that is exactly the future Alfred Nobel hoped to build—not only for himself but for the world.