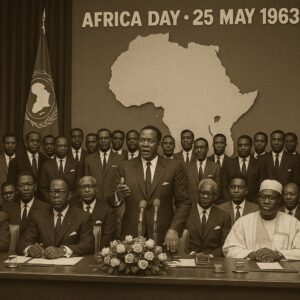

It’s difficult to imagine the weight of a moment like June 3, 1964, without stepping back and understanding the long, painful journey that led up to it. That day, the United States Senate, after months of brutal political wrangling and nearly a century of racial injustice codified into law and daily life, passed the Civil Rights Act—a monumental piece of legislation aimed at upending segregation, dismantling institutional racism, and asserting in law the simple, powerful idea that all Americans deserve equal treatment, regardless of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. But this wasn’t just a bill. It wasn’t just another day of legislative action. It was a pivot point in American history, born of blood, sweat, and years of ceaseless advocacy. It represented a hard-fought victory, not just for lawmakers, but for millions of ordinary people who had marched, spoken out, been arrested, beaten, humiliated, and in some cases, killed, in pursuit of dignity and fairness. The passage of this act would not instantly solve the country’s deeply rooted racial problems, but it would begin the process of reshaping the social and legal fabric of the United States in profound and enduring ways.

The story behind that Senate vote begins long before the gavel came down in Washington, D.C. For nearly a hundred years after the end of the Civil War, African Americans lived under a different kind of oppression, one cloaked not in chains but in laws, customs, and the ever-present threat of violence. The promise of Reconstruction had collapsed by the late 19th century, giving way to the rise of Jim Crow laws in the South—state and local statutes designed explicitly to enforce racial segregation and marginalize Black Americans. These laws touched nearly every aspect of life: where people could eat, which schools their children could attend, what kind of jobs they could hold, whether they could vote. Lynching was a constant specter in many communities, and efforts to achieve political representation or equal opportunity were often met with fierce, sometimes deadly, resistance. For decades, civil rights activists tried to push back, but federal lawmakers and presidents alike were largely unwilling to challenge the status quo, in part out of political self-preservation and in part due to their own biases.

Everything began to change in the aftermath of World War II. African American soldiers returned from the front lines, having fought for freedom abroad only to find it denied to them at home. Their presence sparked renewed calls for equality, and slowly, a national civil rights movement began to take shape. In 1948, President Harry Truman desegregated the armed forces, an early but significant step. But systemic racism remained deeply entrenched, particularly in the South, where Black Americans still faced daily indignities and the constant erosion of their rights. It wasn’t until the 1950s and early 1960s that the movement gained national traction, thanks in part to a new generation of leaders who were determined to confront injustice head-on. Figures like Martin Luther King Jr., Rosa Parks, John Lewis, Ella Baker, Fannie Lou Hamer, and so many others became the public face of the movement, organizing boycotts, sit-ins, voter registration drives, and mass demonstrations. Their courage inspired others to join the cause and forced the country to reckon with its conscience.

Landmark moments defined the movement’s rise: the 1954 Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education declared school segregation unconstitutional, though implementation would take years and face enormous resistance. The Montgomery Bus Boycott of 1955–56, sparked by Rosa Parks’ arrest and led by a young Martin Luther King Jr., showed the power of sustained, nonviolent protest. The 1961 Freedom Rides tested interstate bus desegregation laws and were met with shocking violence, as mobs in Alabama and Mississippi attacked buses and beat passengers while local police looked the other way. In 1963, the nation watched in horror as police in Birmingham, Alabama unleashed fire hoses and dogs on peaceful demonstrators, many of them children. That same year, civil rights leaders organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, where King delivered his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech before a crowd of more than 250,000 people gathered at the Lincoln Memorial.

Public pressure was mounting, and the urgency for comprehensive legislation grew impossible to ignore. President John F. Kennedy, initially hesitant to push civil rights too hard for fear of alienating Southern Democrats, finally proposed what would become the Civil Rights Act in June 1963, just months before his assassination. Speaking on national television, Kennedy asked Americans, “Are we to say to the world—and much more importantly, to each other—that this is the land of the free, except for the Negroes?” His words were clear, but his path forward was fraught with political peril. The legislation stalled in Congress, bogged down by opposition from powerful Southern senators who saw any federal interference with segregation as an existential threat.

When Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, it fell to his successor, Lyndon B. Johnson, to carry the bill forward. Johnson, a Southern Democrat himself, understood the political and cultural complexities of the issue better than most. But he also understood the stakes. Drawing on his personal experiences growing up in poverty in Texas, Johnson had long believed in the power of government to help lift people up. In a speech to a joint session of Congress just days after Kennedy’s death, he declared, “Let us continue,” vowing to honor Kennedy’s legacy by pushing the Civil Rights Act through to passage. It was a gamble that could have cost him politically, but Johnson doubled down. Using his legendary skills of persuasion and political maneuvering—what became known as the “Johnson treatment”—he lobbied, cajoled, threatened, and negotiated with lawmakers on both sides of the aisle. He made it clear that this bill was not just about politics; it was about morality.

By early 1964, the bill had passed the House of Representatives, but the real battle loomed in the Senate. There, a bloc of segregationist Southern senators launched a filibuster of epic proportions. For 60 days, they spoke at length, often irrelevantly, to delay the vote. The filibuster was spearheaded by figures like Senator Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who had already made history by filibustering for 24 straight hours against the 1957 Civil Rights Act. Others, including Senators Richard Russell of Georgia, Robert Byrd of West Virginia, and James Eastland of Mississippi, joined in what became the longest filibuster in Senate history up to that point. They argued the bill violated states’ rights, that it was unconstitutional, that it would disrupt the social order. But at its heart, their resistance was about preserving white supremacy. They feared what true equality would mean in a nation where power had long been unequally distributed.

Outside the Senate chamber, the American people were watching—and acting. Civil rights activists continued their demonstrations across the country. In the spring of 1964, the Freedom Summer campaign was launched in Mississippi, where hundreds of volunteers, many of them white college students, joined Black residents to register voters and set up community programs. The work was dangerous. Within days, three civil rights workers—James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner—disappeared. Their bodies were found six weeks later, buried in an earthen dam. They had been murdered by members of the Ku Klux Klan, with help from local law enforcement. The tragedy shocked the nation and reinforced the urgent need for federal action.

In Washington, Johnson and Senate Majority Leader Mike Mansfield worked tirelessly to break the filibuster. They sought compromise language that would preserve the core intent of the bill while easing concerns among more moderate senators. The turning point came when a bipartisan group known as the “civil rights coalition”—a mix of liberal Democrats and moderate Republicans—managed to gather the votes needed to invoke cloture, effectively ending debate on the bill. On June 10, cloture was achieved by a 71-29 vote, the first time the Senate had successfully overcome a filibuster on a civil rights bill in its history. With debate finally closed, the Senate moved toward a final vote.

And on June 19, 1964—after more than two months of obstruction and delay—the Senate passed the Civil Rights Act by a vote of 73 to 27. The passage of cloture on June 10 had already signaled the outcome, but it was on June 3 that the tide turned irreversibly. The symbolic weight of that day, when the Senate signaled that enough was enough, cannot be overstated. It was the moment the forces of progress broke through the barriers erected by defenders of segregation. It was the moment the long arc of the moral universe curved just a little more sharply toward justice.

President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act into law on July 2, 1964, in a televised ceremony at the White House. Standing beside him were civil rights leaders, members of Congress, and citizens who had fought for this day. Johnson used 75 pens to sign the bill, which were later given away as mementos to those who had played key roles in its passage. In his remarks, Johnson said, “We believe that all men are created equal. Yet many are denied equal treatment. We believe that all men have certain unalienable rights. Yet many Americans do not enjoy those rights. We believe that all men are entitled to the blessings of liberty. Yet millions are being deprived of those blessings—not because of their own failures, but because of the color of their skin.” It was one of the most consequential speeches of his presidency, and it underscored just how much the moment meant—not just legally, but morally.

The law itself was sweeping in its scope. It outlawed segregation in public accommodations—restaurants, hotels, theaters, and parks. It banned employment discrimination by businesses with more than 15 employees. It enforced the desegregation of public schools and gave the federal government the power to withhold funds from institutions that refused to comply. It also strengthened the ability of the Department of Justice to enforce voting rights and pursue legal remedies for civil rights violations. In short, it was a revolutionary assertion of federal power in defense of individual rights.

But while the Civil Rights Act was a major step forward, it was not a panacea. Racism did not vanish with the stroke of a pen. Discrimination adapted, taking on more subtle and insidious forms. Schools continued to be segregated in practice, if not by law. Economic disparities between white and Black Americans persisted. Voting rights, while protected on paper, were still undermined through tactics like literacy tests and poll taxes until the Voting Rights Act of 1965 addressed those loopholes. And in the decades that followed, the struggle for civil rights evolved to meet new challenges—from redlining and mass incarceration to disparities in healthcare, education, and policing.

Even so, June 3, 1964, remains a landmark in the nation’s journey toward equality. It was the day the Senate, long a bastion of obstruction and compromise, finally rose to the occasion and moved the country forward. It was a day forged in the fires of protest and pain, made possible by the bravery of ordinary people who refused to accept injustice as normal. It was a day that honored the memory of those who had paid the ultimate price for freedom, and it was a day that reminded the world that change, however difficult, is always possible when people demand it with courage and conviction.

For millions of Americans, particularly those who had endured generations of humiliation and exclusion, the passage of the Civil Rights Act offered something they had long been denied: recognition. It was a national affirmation that their lives, their dreams, their dignity mattered. And while the work of justice would continue—and still continues—June 3 was the moment the nation said, with clarity and commitment, that it was ready to begin a new chapter. A chapter not defined by who we had been, but by who we aspired to become.