In the crisp chill of a winter morning in South Africa, August 5, 1962, the wheels of a police vehicle hummed down a quiet road near Howick in Natal. Inside sat a tall, dignified man wearing a chauffeur’s cap, assuming the role of a humble driver. But this was no ordinary man, and this was no ordinary drive. The man was Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela—lawyer, freedom fighter, father of five, and the symbolic heart of a movement that had already begun shaking the roots of apartheid. His arrest that day would become more than a simple act of police enforcement; it would ignite a legacy of resistance, resilience, and revolution that transformed South Africa and inspired the world.

Nelson Mandela’s journey to that car ride in 1962 had already been marked by defiance and danger. Born in 1918 in the rural village of Mvezo, Mandela came from royal lineage among the Thembu people. Yet his life was not destined for ceremonial titles or quiet deference. Instead, he became the voice of millions denied dignity under apartheid—a racial segregation system so entrenched and brutal that even everyday actions, like walking through a door meant for whites, could end in arrest or violence. The apartheid regime wasn’t simply a political framework; it was a psychological prison. It operated with precision, using laws to split families, crush communities, and instill fear so deeply that silence became survival. But Mandela refused silence.

By the late 1950s and early 1960s, Mandela had already made a name for himself as a rising figure in the African National Congress (ANC), co-founding its militant offshoot, Umkhonto we Sizwe (“Spear of the Nation”). Frustrated by decades of peaceful resistance yielding only harsher oppression, Mandela and others concluded that non-violent protest had reached its limit. Sabotage—not terrorism, but strategic attacks on infrastructure—became their chosen path. Mandela traveled across Africa and even to London, gathering support and training. When he returned to South Africa, he did so under the cloak of secrecy, assuming false identities and moving stealthily from one safe house to another. To the authorities, he became known as “The Black Pimpernel.”

It was betrayal, as is often the case in the annals of revolution, that led to Mandela’s capture. CIA involvement is widely speculated—an agent tipped off South African authorities about Mandela’s whereabouts, a reflection of Cold War fears that African liberation movements might tilt toward Soviet influence. But on August 5, 1962, none of that mattered to Mandela as armed police flagged down his car and placed him under arrest. They charged him with inciting workers’ strikes and leaving the country illegally, but in truth, they had caught the man they feared most—the man who had refused to be intimidated into submission, who had evaded their grasp for 17 months, and who stood as the soul of South Africa’s freedom struggle.

Mandela was sentenced to five years in prison in November 1962. But this was only the beginning. As the government investigated further, it uncovered documents linking him and others to Umkhonto we Sizwe activities. In 1963, the infamous Rivonia Trial began—a proceeding that would define Mandela’s global image as a moral giant. During the trial, Mandela stood not merely as a defendant, but as an orator of justice, delivering his legendary three-hour speech from the dock, culminating in the unforgettable line: “I have cherished the ideal of a democratic and free society… It is an ideal for which I am prepared to die.”

The court did not sentence him to death, but the verdict was nearly as chilling: life imprisonment. On June 12, 1964, Mandela and his comrades were sent to Robben Island, a bleak outcrop off the coast of Cape Town. There, he would spend the next 18 of his 27 years in prison, subjected to hard labor in a lime quarry, forbidden from touching his children, restricted to one visitor every six months and one letter every three. Prison was intended to break him, to erase him from memory, to make an example of him. Instead, it elevated him. Mandela turned his cell into a classroom, a strategic center, and a place of transformation—not only for himself but for his jailers.

Over the decades, something extraordinary happened. While South Africa’s government clung to its racist policies with ever more violence, the imprisoned Mandela became a living symbol of hope. Posters with his name and silhouette circled the globe. His calm resilience, the poetry of his courtroom speeches, and the dignity he maintained in the face of deliberate dehumanization made him a martyr in real-time. The cry “Free Nelson Mandela” echoed in stadiums, concerts, parliaments, and student protests from London to Lusaka, from Sydney to Stockholm. But for the man behind the prison bars, life remained regimented and painful. Yet even in confinement, Mandela negotiated. He learned Afrikaans, the language of his captors. He studied their culture. He sought to understand them—not to appease them, but to build a bridge he could one day cross.

By the 1980s, global pressure mounted. Sanctions hit South Africa’s economy. Cultural and academic boycotts isolated the nation. Internal resistance intensified, and the cost of maintaining apartheid became too high even for its most diehard supporters. The state tried to strike deals with Mandela, offering conditional release if he would denounce the armed struggle. He refused. He would not be freed simply to endorse a partial, unjust peace. When negotiations did finally begin in earnest in the late 1980s, Mandela’s role was indispensable. He was the man the regime had tried to bury, only to discover he was a seed.

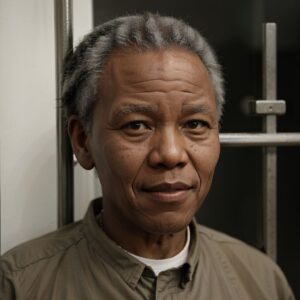

On February 11, 1990, Nelson Mandela walked out of Victor Verster Prison with his fist raised. He was older, his hair grayer, his gait slower—but his spirit was unshaken. The moment remains etched in history, not just as a personal victory but as a tidal shift. The man arrested in secret on a lonely road now walked openly before the world, welcomed as a hero, a president-in-waiting, and the father of a democratic South Africa.

The years that followed his release were complex. Mandela did not return to vengeance but to reconciliation. In 1994, he was elected South Africa’s first Black president in the nation’s first fully representative election. His leadership was defined by forgiveness, vision, and humility. He refused to serve more than one term, setting an example of democratic transition. And he remained, until his death in 2013, a symbol of what humans can endure and overcome.

To reflect on Mandela’s arrest in 1962 is not simply to note a moment of repression. It is to recognize the start of a crucible—one that forged a leader of rare moral authority. It is to confront the fact that true change often begins in the shadows, behind bars, in silence, and under immense suffering. And it is to understand that history does not always pivot on the loudest moment, but sometimes on the quiet resolve of one man refusing to break.

Mandela’s story is no myth, though it often feels mythic. He was not perfect—he was once a militant, he struggled in marriage, and he carried the burdens of leadership heavily. But what makes him enduring is precisely that humanness. He evolved. He remained rooted in principle while being willing to grow, to listen, and to seek peace without compromising justice. In a world still riven by division, his life offers not just inspiration but instruction.

Today, South Africa is still grappling with inequality, corruption, and the long tail of apartheid. Mandela never claimed his struggle was over. But he gave the country the tools to continue it—a constitution built on rights, a legacy of dialogue over destruction, and the memory of a man who proved that even the darkest prison cannot hold the light of freedom.

August 5, 1962, is the day the South African regime tried to silence its greatest critic. Instead, it enshrined his voice in the conscience of humanity. Behind those bars, Nelson Mandela became more than a man—he became a movement.