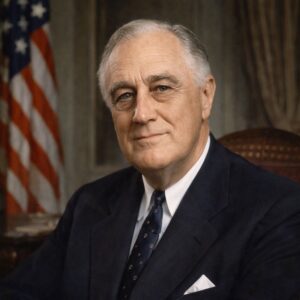

I’ve always been fascinated by Franklin D. Roosevelt, but not in a straightforward way. It’s not just his accomplishments or his leadership during World War II that draw me in – although those are certainly impressive. What really gets my attention is the complexity of his personality and the contradictions within him.

Growing up, I read about FDR’s disability and how it affected his public image. I remember feeling a mix of awe and discomfort as I learned about how he hid his struggles with polio from the public eye. On one hand, I admired his determination to continue serving despite his physical limitations. But on the other hand, I wondered why he felt the need to conceal something that was such a significant part of his identity.

As an only child of parents who always emphasized my independence and ability, FDR’s decision to hide his disability from the public seems both understandable and frustrating. I can see how it would be tempting to present oneself as strong and capable in order to avoid judgment or sympathy. But at the same time, I worry that by hiding this aspect of himself, FDR may have missed out on opportunities for connection with others who might have understood him better.

I’m struck by the tension between FDR’s public persona – confident leader, charming statesman – and his private struggles. It makes me think about how we present ourselves to the world versus how we really feel. Do we hide our vulnerabilities in order to fit in or achieve our goals? Or do we risk being perceived as weak or flawed by revealing them?

One of FDR’s most famous speeches, the 1941 State of the Union address – also known as the “Four Freedoms” speech – is often cited as a highlight of his presidency. In it, he envisions a world where people have freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. What I find compelling about this speech is not just its eloquence or its vision for a better future, but the fact that FDR himself was deeply aware of the fragility of these freedoms.

As someone who grew up in a relatively privileged community, it’s easy to take these freedoms for granted. But listening to FDR talk about them as something worth fighting for makes me realize how easily they can be taken away. His words make me think about my own place within this country and the world – not just as an individual, but as someone with a voice that can either amplify or ignore the struggles of others.

I’m not sure what it is about FDR’s story that resonates with me so deeply. Maybe it’s because he represents a paradox I’ve struggled with myself: the desire to be seen and accepted for who you truly are versus the pressure to conform to societal expectations. Perhaps it’s his willingness to challenge traditional norms and push boundaries, even if it meant facing criticism or ridicule.

As I continue to read about FDR and reflect on my own reactions, I’m left with more questions than answers. What does it mean to be strong, anyway? Is it possible to show vulnerability without being seen as weak? And what happens when we try to hide parts of ourselves from the world – do we risk losing touch with our authentic selves in the process?

I don’t have any clear conclusions or insights about FDR’s life. But by exploring these questions and complexities, I’m forced to confront my own biases and assumptions about leadership, identity, and what it means to be human. And that, for now, feels like a more honest and interesting place to start.

As I delve deeper into FDR’s life, I find myself wondering about the relationships he maintained behind closed doors. His marriage to Eleanor Roosevelt is often cited as one of the most enduring partnerships in American history, but I’m struck by the power dynamics at play. Eleanor was not only his wife, but also a close advisor and confidante – a position that’s both remarkable and complicated.

I think about my own relationships with my parents, particularly my mother. We’ve always had a strong bond, but as I’ve grown older, I’ve begun to realize the ways in which she’s also been a source of tension for me. She wants me to be independent, just like FDR’s upbringing shaped his sense of self-reliance, but sometimes her expectations feel suffocating. I wonder if Eleanor Roosevelt ever felt similarly trapped by her role as First Lady and wife.

FDR’s relationships with others are also fascinating to me – particularly his friendships with men like Harry Hopkins and Frances Perkins. These men were not only close advisors, but also confidants who helped him navigate the demands of the presidency. I think about my own friendships and how they’ve evolved over time. As I’ve grown older, I’ve started to prioritize deeper, more meaningful connections with people who understand me on a fundamental level.

This brings me back to FDR’s speeches – particularly his famous phrase “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself.” It’s easy to dismiss this as a soundbite or a platitude, but for FDR, it was a deeply personal mantra. He knew that fear could be paralyzing, that it could hold you back from taking risks and pursuing your goals. I think about my own fears – the ones I’ve faced in college, the ones I’m facing now as I navigate this post-grad world.

FDR’s story makes me realize how much we’re all fighting our own battles, often behind closed doors or with a mask of confidence. We present ourselves to the world as strong and capable, but inside, we’re just as scared and uncertain as everyone else. It’s a humbling thought, one that I’m not sure I’ve fully absorbed yet.

As I continue to explore FDR’s life, I’m left with more questions about what it means to be human – our strengths and weaknesses, our fears and desires. What does it mean to be vulnerable in public, without sacrificing your sense of self? And how do we balance the need for connection with others with the desire to maintain our own autonomy?

I’m not sure I have any answers yet, but by asking these questions, I feel like I’m getting closer to understanding FDR – and maybe even myself.

One of the things that’s struck me about FDR’s life is his relationship with time. As a man who contracted polio in his late 20s, he was acutely aware of the fragility of time and the importance of making every moment count. In many ways, this sense of urgency drove him to achieve great things – from leading the country through two wars to implementing sweeping reforms like Social Security.

But it’s not just FDR’s accomplishments that fascinate me; it’s also his approach to time itself. He was a man who lived in the present, always pushing forward with a sense of purpose and determination. And yet, he was also deeply aware of the past – its lessons, its mistakes, and its triumphs.

As someone who’s recently graduated from college, I feel like I’m struggling to find my own place in time. I’ve got a degree, but what does it mean? What am I supposed to do with this blank slate that stretches out before me? FDR’s story makes me realize just how much pressure there is to achieve great things, to make the most of every moment.

But what if I don’t know what I want to do? What if I’m still figuring out who I am and where I fit in the world? Does that mean I’m failing somehow? FDR’s life suggests otherwise – that it’s okay not to have all the answers, that it’s okay to take risks and try new things.

I think about my own fears and doubts – the ones that whisper in my ear, telling me I’m not good enough or that I’ll never amount to anything. FDR’s story makes me realize just how much of a role fear plays in our lives – the way it can hold us back from pursuing our dreams, from taking risks.

And yet, at the same time, his life also suggests that fear is something we can overcome. That by facing it head-on, by confronting our doubts and insecurities, we can find the strength to move forward.

I’m not sure what this means for me right now – whether I’ll end up following in FDR’s footsteps or forging my own path entirely. But as I continue to explore his life and legacy, I feel like I’m slowly starting to untangle some of the complexities that have been weighing on me. Maybe that’s the point of all this reflection – not to find answers, but to ask new questions, to seek out a deeper understanding of myself and the world around me.

As I delve deeper into FDR’s life, I’m struck by his ability to pivot in the face of adversity. His presidency was marked by numerous challenges, from the Great Depression to World War II, but he consistently demonstrated an unwavering commitment to finding solutions. This trait resonates with me as someone who often finds themselves at a crossroads, unsure which path to take.

FDR’s willingness to adapt and evolve is something I admire greatly. He didn’t shy away from trying new approaches or embracing unconventional ideas, even when they were met with resistance. In contrast, I often find myself stuck in my own ruts, hesitant to deviate from the familiar. FDR’s example encourages me to be more open-minded, to trust that uncertainty can lead to growth and innovation.

One of the aspects of FDR’s leadership that continues to fascinate me is his use of storytelling as a tool for communication. He was a masterful storyteller, able to weave complex ideas into compelling narratives that resonated with the American people. I’ve always been drawn to writing as a means of exploring my own thoughts and emotions, but FDR’s approach shows me the power of using narrative to connect with others.

As someone who’s still navigating their post-grad identity, I’m struggling to find my own voice – both in terms of what I want to say and how I want to say it. FDR’s example suggests that storytelling can be a powerful way to express myself, to convey the complexities and nuances of human experience. By embracing this approach, I may be able to tap into a deeper sense of purpose and connection with others.

FDR’s life also makes me think about the role of privilege in shaping our experiences and perspectives. As a member of the American elite, he enjoyed a level of comfort and security that many people could only dream of. And yet, despite these advantages, FDR was acutely aware of the struggles faced by those around him – from the working-class Americans who were struggling to make ends meet during the Great Depression to the marginalized communities who were fighting for their rights.

This awareness is something I admire greatly, as it suggests that even in the midst of privilege, one can remain attuned to the needs and experiences of others. As someone who’s grown up with a certain level of comfort and security, I’ve often felt guilty about my own privilege – like I’m somehow complicit in the systems of oppression that perpetuate inequality.

FDR’s life encourages me to see my privilege not as something to be ashamed of, but rather as an opportunity to use my position for good. By acknowledging the advantages I’ve been given and using them to amplify the voices and experiences of others, I can work towards creating a more just and equitable world – one that recognizes the value and dignity of every individual.

I’m not sure where this will take me or what specific actions I’ll take, but FDR’s example inspires me to be more mindful of my own privilege and to use it as a force for positive change. By embracing this responsibility, I may be able to make a difference in the world – even if it’s just in small, incremental ways.