On an otherwise ordinary Sunday morning in Hawaii, when the world seemed quiet and the horizon glowed with the soft colors of sunrise, an event unfolded that would shatter the rhythm of daily life and alter the course of history forever. December 7, 1941, was meant to be peaceful—a day for sailors to rest, for families to gather, for soldiers to take a rare breath between drills. Yet, in a matter of minutes, calm transformed into chaos, and the United States found itself thrust into the center of a global conflict it had tried for years to avoid. The attack on Pearl Harbor wasn’t merely a tactical strike; it was a moment that tore through America’s consciousness, awakening a nation and steering it down a path that would define the 20th century.

But to understand the shock and devastation of that morning, one must look back at the decades of tension simmering beneath diplomatic language and political maneuvering. Relations between Japan and the United States had been deteriorating long before the bombs fell. Japan, seeking resources and dominance in Asia, saw itself as a rising power constrained by Western influence. The United States, wary of Japan’s ambitions, used economic pressure—particularly through embargoes—to curb its expansion. These sanctions, especially the American oil embargo, cut deep. Oil was the lifeblood of Japan’s military machine, and without it, the empire’s ambitions would wither before ever reaching fruition.

Resentment had been building in Japan for years. After World War I, the Treaty of Versailles left Japan feeling slighted and excluded from the global stage it believed it deserved. Western powers had dictated the postwar order, carving up influence and privileges in Asia, and Japan believed it had been denied its rightful place among them. These grievances fueled nationalism, militarism, and a sense of destiny that the Japanese government would use to justify its aggressive expansion through China and Southeast Asia.

The United States watched these developments with increasing concern. The invasion of China, the occupation of Manchuria, and the forced march through Southeast Asia signaled a Japan willing to use force to claim territory and resources. America, committed to protecting its own interests in the Pacific and supporting China through various aid programs, felt compelled to respond. In 1940 and 1941, sanctions escalated—freezing Japanese assets, restricting exports, and finally imposing the devastating oil embargo. Without oil, Japan’s military strength would evaporate within months. Its leaders faced a grim reality: submit to American pressure and abandon their imperial ambitions, or strike decisively before their war machine ran dry.

They chose the latter.

In secret meetings, Japan’s military strategists crafted a daring plan—one that would aim to cripple the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor in a single, devastating blow. This operation, meticulously designed under the leadership of Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, sought to neutralize American naval power long enough for Japan to secure the territories it desired. If successful, Japan hoped, the United States would be forced into negotiation rather than war.

As the sun rose on December 7, American sailors began their day unknowingly beneath the shadow of incoming disaster. Some were preparing for church. Others were still asleep. Routine filled the base: engines being checked, flags being raised, breakfast being served. Life seemed simple, predictable, ordinary.

Then the sky darkened with the silhouettes of Japanese aircraft.

The attack was swift, brutal, and shockingly effective. The first wave of bombers tore through the sky just before 8 a.m., dropping torpedoes and armor-piercing bombs onto the anchored battleships below. The USS Arizona exploded with such violent force that entire sections of the ship disintegrated instantly, taking the lives of more than a thousand crew members in seconds. The USS Oklahoma capsized, trapping hundreds inside its hull. Smoke filled the air as flames engulfed ships and oil spread across the water, turning the harbor into a burning graveyard.

American forces scrambled to respond, but confusion and lack of preparation hindered their efforts. Many pilots were killed before they could reach their planes. Anti-aircraft guns fired frantically through smoke and fire, but the precision and coordination of the Japanese attack overwhelmed the defenses. By the time the second wave swept through, the destruction was nearly complete.

When the final explosions faded and the sky quieted, Pearl Harbor lay in ruins. More than 2,400 Americans had been killed. Battleships smoldered beneath the waves. Aircraft were reduced to twisted metal across the airfields. The Pacific Fleet, the pride of American naval power, had suffered catastrophic losses.

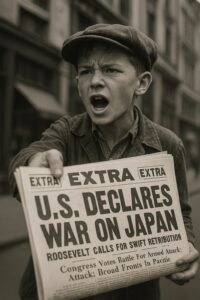

News of the attack spread across the United States with dizzying speed. Radios interrupted Sunday programming with urgent bulletins. Newspapers rushed out extra editions. Families gathered around living-room radios, listening in stunned silence as reporters described the devastation a world away. The sense of disbelief quickly gave way to outrage. Japan’s attack was widely perceived as treacherous—a strike launched while diplomats still engaged in negotiations in Washington, D.C. The American public, previously divided on whether to support involvement in World War II, united almost instantly.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt, known for his steady leadership and resonant voice, addressed Congress the next day in what would become one of the most iconic speeches in American history. His words were deliberate, powerful, and infused with the gravity of the moment:

“December 7th, 1941—a date which will live in infamy.”

The phrase echoed across the nation. It still echoes today. Roosevelt spoke not just to lawmakers, but to every American hurting, angered, and afraid. He described the attack as deliberate and unprovoked, and he called for action—not merely as retaliation, but as a moral imperative.

Congress declared war on Japan almost unanimously.

America had entered World War II.

From that moment on, the nation transformed itself at a staggering pace. Young men enlisted in droves. Factories retooled for war production. Women entered the workforce in unprecedented numbers, filling roles once reserved for men. American industry became a juggernaut, producing ships, tanks, planes, and ammunition at a rate the world had never seen. A country still struggling from the aftershocks of the Great Depression became the engine of the Allied victory.

The attack on Pearl Harbor also set off a chain reaction across the world. Germany and Italy declared war on the United States, pulling America fully into the global conflict. Meanwhile, Japan expanded across Asia, capturing territories and pushing deeper into the Pacific. But its initial success was short-lived. The United States recovered quickly, rallying its forces and striking back with fierce determination. Battles like Midway, Guadalcanal, and Leyte Gulf turned the tide of the war, slowly but steadily pushing Japan back toward its own shores.

The war in the Pacific would become one of the most brutal theaters of combat in human history. Island by island, American forces fought through unforgiving jungles, entrenched fortifications, and kamikaze attacks. The cost in lives was staggering. Yet America persisted, driven not only by strategy but by memory—the memory of Pearl Harbor, of the lives lost, of the shock and betrayal that had galvanized the nation.

When the war finally ended in 1945 after the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the world stood transformed. Japan, devastated and demoralized, surrendered. The United States emerged as a global superpower. The geopolitical landscape reordered itself around new alliances and tensions, many of which still shape international relations today.

But Pearl Harbor remains, even decades later, a symbol etched deeply into the American consciousness. It represents vulnerability and resilience, tragedy and transformation, loss and determination. The memorials that stand over the sunken ruins of the USS Arizona remind visitors that the morning of December 7 was not merely an attack—it was a turning point. A catalyst. A moment when history shifted and the world was never the same again.

To reflect on Pearl Harbor is to acknowledge the fragility of peace, the unpredictability of conflict, and the extraordinary capacity of nations to rise from devastation. It is a reminder that history is shaped not only by decisions made in grand halls of diplomacy, but by the sacrifices of individuals whose names may never appear in textbooks. Their memory lives on in the stories retold, the lessons remembered, and the determination to never allow such a tragedy to repeat itself.

In Roosevelt’s immortal words, December 7, 1941, truly is “a date which will live in infamy.” Not just as a chapter in history, but as a reminder of courage, unity, and the enduring will of a nation that refused to be broken.