When the First Session of the United States Congress convened in Washington, D.C., on November 17, 1800, something far greater than a routine legislative gathering took place. It was a moment when an idea became a reality, when a theoretical capital—sketched on maps, debated in halls, argued over in newspapers, and surveyed in muddy fields—suddenly acquired a heartbeat. The meeting of Congress in the unfinished Capitol building marked the moment when Washington D.C. ceased to be a distant vision and became a center of national identity, authority, and ambition. It was the moment when the United States government anchored itself physically and symbolically to a place built not from history but from intention. And in that moment, amid scaffolding, raw lumber, wet paint, and a persistent smell of plaster dust, the young republic stepped into its next chapter.

To appreciate the significance of that first congressional session in Washington, one must remember how fragile and experimental the United States still was. Barely a dozen years had passed since the Constitution was ratified. The Revolutionary War was a fresh memory. The wounds of political division, which had deepened during the presidencies of George Washington and John Adams, were already visible, some of them raw and bitter. The nation was still trying to define what it meant to function under a federal system that attempted to balance liberty with order, local autonomy with national unity. And underlying it all was the persistent question that had haunted the government since its inception: Where should the capital of this new nation be?

The road to Washington as the capital was long, tense, and full of political maneuvering. In the early years of independence, the Continental Congress had wandered like a nomadic tribe, meeting in Philadelphia, New York, Princeton, Annapolis, and even Trenton. Each location reflected political pressure, geographic convenience, or crisis management. But by the late 1780s, it was clear that such instability was unsustainable. A permanent capital was needed—one that would serve not only as a seat of government but as a symbol of the nation’s future.

Washington D.C. emerged from this need and from the compromises that defined the early republic. The Residence Act of 1790, engineered by the political negotiation between Alexander Hamilton, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison, established that the capital would sit on the Potomac River. The choice was strategic: it placated southern states wary of northern economic dominance while keeping the capital at a safe distance from any one state’s influence. The land itself—farmland, forests, rolling hills—offered no grandeur at the time. It was muddy, humid, mosquito-filled, and sparsely populated. But for President George Washington, who oversaw the development personally, it offered something more powerful than immediate elegance: it offered neutrality, potential, and symbolism.

By 1800, however, Washington D.C. was still very much a work in progress. The President’s House—later called the White House—stood largely finished but surrounded by wilderness. Streets existed mostly on paper. Roads were rough, unpredictable, and often impassable after rain. Boarding houses served as the main lodging for members of Congress, many of whom complained about damp walls, poor food, and insects that seemed determined to share their rooms. The Capitol building was only partially completed, with the north wing usable but the rest still under construction. Workers, tools, and piles of building material were constant companions to the lawmakers who would soon gather there.

It was into this half-formed capital that Congress arrived in November 1800. Their journey was long, uncomfortable, and, for many, reluctant. Members traveled by carriage, horseback, ferry, and even on foot. Some found themselves slogging through muddy roads or navigating flooded riverbanks. When they finally reached the city, what they encountered was hardly the majestic center of power they might have imagined. The Capitol itself sat atop Jenkins Hill—later called Capitol Hill—like a grand but unfinished promise. One congressman described the landscape as “a city of magnificent distances,” while another remarked that the government had moved from “a palace in Philadelphia to a pigsty in Washington.” And yet, beneath the complaints, there was an undeniable sense of historic weight.

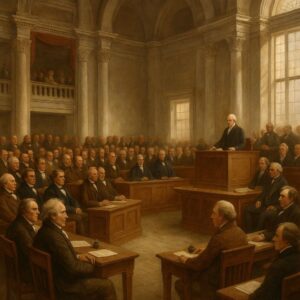

When Congress gathered in the Senate Chamber of the Capitol’s north wing, the atmosphere was charged with both anticipation and uncertainty. The chamber itself was elegant but surrounded by reminders of the city’s incompleteness. The sound of hammers and saws drifted through hallways. Cold drafts seeped through gaps in walls. Furnishings were sparse. But the symbolism of the moment overshadowed the imperfections. For the first time, Congress met in the capital designed specifically for the federal government—purpose-built, neutral, forward-facing.

The convening of Congress in Washington would have profound implications. First, it signaled the endurance of the constitutional system. The government had survived its infancy, weathered crises, and now completed a symbolic relocation that solidified its permanence. Second, it established the precedent that Washington D.C.—with all its flaws and future potential—would be the nation’s political heartbeat. Third, it set the stage for one of the most consequential elections in American history, the election of 1800, which unfolded at the same time Congress was settling into the new capital.

That election, pitting John Adams against Thomas Jefferson, was a bitter, divisive, and transformative contest. While Congress opened in Washington, the nation was in the throes of political warfare. Newspapers hurled insults, candidates exchanged accusations, and voters grappled with competing visions of America’s soul. Federalists feared Jefferson would dismantle the nation’s fragile institutions; Democratic-Republicans accused Adams of aspiring to monarchy. The tension seeped into the halls of the Capitol, creating an undercurrent of political electricity as the legislative session unfolded.

For the men who sat in that first congressional session, the capital’s stark surroundings seemed almost a metaphor for the state of the nation. The city was unrefined, unpolished, and challenging to inhabit—much like the country itself, which was still defining its identity, norms, and political culture. Yet the potential was unmistakable. The Capitol, though unfinished, possessed a certain gravity. Its broad steps, stately columns, and elevated position overlooking the Potomac River suggested not just where the nation was, but where it intended to go.

The first session in Washington required the members of Congress to adapt quickly. They lodged in boarding houses grouped by political affiliation, which only heightened partisanship. Daily life was simpler, harsher, and more communal than in Philadelphia or New York. Newspapers arrived irregularly. Supplies were limited. Social gatherings took place in modest taverns or small parlors rather than grand ballrooms. Many members missed the culture and comforts of Philadelphia, with its libraries, theaters, and refined amenities. But in this rough environment, something new developed: a shared sense of purpose grounded not in luxury but in the work of governance itself.

As Congress settled into its new home, it tackled the pressing issues facing the nation. Debate raged over foreign policy, military preparedness, taxes, the judiciary, and the disturbing implications of the recent Alien and Sedition Acts. Members wrestled with questions about federal authority, the balance of power among branches, and the proper role of political parties. The challenges were immense, yet the setting amplified the stakes. Conducting these debates in Washington, rather than Philadelphia, gave them a more permanent flavor. Decisions made in the Capitol felt less like temporary measures and more like foundational precedents.

Outside the Capitol, Washington D.C. grew slowly but steadily. Workers continued building streets, homes, and government structures. President Adams moved into the Executive Mansion—the future White House—shortly before Congress arrived. He famously wrote to Abigail Adams that the house was “habitable” but still very uncomfortable, with unfinished rooms and cold drafts. Yet even Adams, often critical of Washington’s conditions, recognized the symbolic significance of moving into the presidential residence. He understood that history was unfolding, brick by brick, and that future generations would look back on these early hardships as the necessary cost of establishing a capital worthy of a republic.

One of the most compelling aspects of the first congressional session in Washington was the atmosphere of humility that accompanied the grandeur of the moment. There were no lavish ceremonies, no triumphal processions, no decorative pageantry. The city was too raw, too new, too simple to accommodate such displays. Instead, the lawmakers’ presence itself became the event. Their physical gathering in Washington validated the experiment of a purpose-built capital. Their debates echoed through unfinished halls like the early heartbeat of a democratic institution still learning how to walk.

Behind the political drama and logistical challenges was a deeper truth: the move to Washington marked the completion of a dream that had begun decades earlier. George Washington, who had lent his name to the city, never lived to see Congress convene there. But his vision of a strong, stable, centralized seat of government was realized in that first session. The city, still little more than a scattered village, represented unity in a nation struggling to hold itself together. It was a commitment to the idea that governance required not only ideals but also place—a physical space where lawmakers could gather, deliberate, and embody the collective will of the people.

As weeks passed, Congress adjusted to its new environment. Members began to see promise where they had once seen only inconvenience. They watched the city’s landscape slowly transform as new buildings appeared, muddy roads improved, and social life adapted to the rhythms of the capital. The air of transience faded. The Capitol became familiar. Washington became home.

The first session of Congress in Washington did not end political division—if anything, the coming years would prove that partisanship would become a defining feature of American democracy. Yet the session achieved something equally vital: it anchored the United States government in a permanent capital where institutions could grow, mature, and assert authority with continuity. In the decades that followed, Washington D.C. would expand into a city of monuments, museums, stately buildings, and grand avenues. But its beginnings—those rough, uncertain, quietly monumental days of 1800—remained etched in the spirit of the place.

Looking back, the significance of that first gathering becomes clearer. It was not simply the opening of a legislative session. It was the nation’s declaration that it intended to endure. It was a step away from improvisation and toward permanence. It was a moment when the American experiment became a little less experimental and a little more institutional. The lawmakers who trudged through mud to reach the Capitol could not know how vast the city around them would one day become, or how intensely its decisions would shape the world. But they understood that they were building something enduring, something larger than themselves.

The First Session of Congress in Washington D.C. was a beginning—the beginning of a capital, a symbol, a center of civic life, and a place that would witness triumphs, crises, debates, celebrations, and transformations for more than two centuries. It was the moment when Washington took its first breath as the heart of American governance.

And like all first breaths, it was imperfect, fragile, and full of possibility.