At 9:02 a.m. on September 2, 1945, the morning in Tokyo Bay felt like a held breath. The sea was pewter under an overcast sky, the air still with that strange quiet that follows thunder. Allied battleships and carriers crowded the water like punctuation marks at the end of a very long sentence, their decks lined with sailors standing shoulder to shoulder, dress khaki and blues turning into a human shoreline. And in the center of it all, moored like a stage, sat the USS Missouri—BB-63—her teak deck scrubbed, her brass polished, her bulkhead draped with an American flag that had once flown with Commodore Perry when he sailed into Japan nearly a century earlier. History rarely arranges theater so neatly. That day, it did.

At 9:02 a.m. on September 2, 1945, the morning in Tokyo Bay felt like a held breath. The sea was pewter under an overcast sky, the air still with that strange quiet that follows thunder. Allied battleships and carriers crowded the water like punctuation marks at the end of a very long sentence, their decks lined with sailors standing shoulder to shoulder, dress khaki and blues turning into a human shoreline. And in the center of it all, moored like a stage, sat the USS Missouri—BB-63—her teak deck scrubbed, her brass polished, her bulkhead draped with an American flag that had once flown with Commodore Perry when he sailed into Japan nearly a century earlier. History rarely arranges theater so neatly. That day, it did.

On the deck, a plain table sat under a green felt cover—nothing ornate, nothing that would compete with the moment. A pair of black inkstands, a fountain pen, a neat stack of documents, and two empty chairs. Nearby, General Douglas MacArthur stood in khaki, open collar, sunglasses, all posture and angles, the very shape of declaration. Admiral Chester Nimitz waited with the relaxed intensity of a man who has carried an ocean on his shoulders for four years. Arrayed behind and around them were the representatives of nations that had bled and broken and borne the weight: Britain’s Admiral Sir Bruce Fraser, China’s General Hsu Yung-chang, the Soviet Union’s Lieutenant General Kuzma Derevyanko, Australia’s General Sir Thomas Blamey, Air Vice-Marshal Leonard Isitt of New Zealand, General Philippe Leclerc for France, Admiral Conrad Helfrich for the Netherlands, and Colonel Lawrence Cosgrave of Canada. Cameras clustered like curious birds. On the waterline, launch craft bobbed, as if even the small boats wanted a better view of the world righting itself.

Then the Japanese delegation climbed aboard. They came in morning coats and striped trousers, black formal shoes polished to a mirror. Leading them was Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu, top hat in hand, a cane under his right arm to relieve the pain of an old wound that made every step a small wince. Beside him was General Yoshijirō Umezu, the Army’s Chief of Staff, his face a practiced stillness. They did not look like victors or heroes, or even villains; they looked like men who had arrived at the end of a road that had never led anywhere else. The wind worried a corner of the surrender document as if impatient for the ink.

MacArthur spoke—measured phrases hammered flat by the steel of the ship and the sea. He said this ceremony was not a victory party, but a return to reason. He said he hoped a better world would emerge from the blood. It was the kind of speech that is easier to make when the guns are silent, but it mattered anyway because sometimes the world needs words more than it needs hardware. Then the choreography began: the Japanese signatories stepped forward first, because the order of names on paper must match the order of history. Shigemitsu lowered himself carefully into the chair, set his top hat on the table, laid his cane alongside the inkstand, and took up the pen. The scratch of nib on paper was too soft to hear over the water and the cameras and the lungs of thousands, but you could almost feel it in your teeth. That line of ink was the narrowest bridge ever built between war and peace, and somehow it held.

Within minutes, Umezu added his name. The Allies followed, MacArthur first with a pen he would later give away in pieces as souvenirs for those who had borne the burden; then Nimitz for the United States; then the others, in a roll-call of nations that had learned new meanings for the word “ally.” There was a small, human error: Colonel Cosgrave, half blind from a wartime injury, signed on the wrong line, nudging the signatures beneath his downward by one. A witness leaned in to correct him. MacArthur shrugged and smiled. After years of industrial catastrophe measured to the second and the bolt, this little misalignment felt almost like a blessing—a reminder that the future we were entering was one where mistakes could be mended with pencil marks and courtesy rather than artillery.

But the meaning of the morning wasn’t on that table alone. It was scattered across the decks in a thousand private stories: a radio operator from Kansas who had learned to sleep between general quarters, a Marine from Harlem whose last letter home still had sand in the envelope, a shipfitter from Manila who had carried another man through smoke. Some of them had names for that day—V-J Day in the American lexicon, simply “the surrender” for others. For many, September 2 was less a celebration than an exhale. The sailor beside the starboard rail held his breath longer than he meant to, then let it out and realized his hands were shaking. He didn’t raise his cap or shout; he just pressed his palm to the warm teak and told himself the wood was real.

If you pan the camera back enough, you can see the entire decade folding toward that deck: the invasion of Manchuria in 1931, the long grind through China, Pearl Harbor, the island chain strung with names that will never again mean only geography—Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan, Leyte Gulf, Iwo Jima, Okinawa. You see factory floors in Detroit and Osaka; you see ration cards and code books and the steady beat of propellers that made the Pacific smaller than anyone had believed. And if you pan wider still, you glimpse the ruins in Europe and the trains that never came back and the cities made of bricks and ash. The Missouri’s deck held the Pacific war’s ending, but the relief radiated across oceans.

Think about the weather that morning: a blanket of gray cloud, as though the sky preferred to mute itself. Photographs from the ceremony have that calm, even light that portrait photographers dream of—no harsh shadows to collapse eyes into caves. It’s as if the day refused drama, at least the kind you can see, because the drama had already exhausted itself. The Pacific had eaten years; the calendar had become a stone wheel. And then, for an hour, everything was still enough for handwriting to matter.

“History is made by signatures and sergeants,” an old Navy chief liked to say. He meant that the world turns when leaders agree and when ordinary people execute. In Tokyo Bay, both kinds of history were busy. The signatures were neat; the sergeants had already done their part. You cannot have a surrender without people who refused to surrender when it cost the most. Imagine a 19-year-old gunner’s mate who had never been 19 in any ordinary way, a nurse whose hands could tie a tourniquet in the dark, a codebreaker who translated a signal that saved a convoy in seas rougher than anger. They had ferried the world to this deck plank by plank, heartbeat by heartbeat. They were not on camera. The camera rarely finds the foundation.

Some observers called the ceremony “mercifully brief.” That mercy mattered. War has a way of turning every human act into a prolonged formality, a queue that always ends in an office where someone says “Come back tomorrow.” The surrender on Missouri was the opposite—finite, precise, a bureaucracy refitted for grace. The Japanese delegation departed quickly. The Allied representatives saluted. The band played. Bells rang across the fleet, voices rolled like a tide, and then—quiet again, as if everyone wanted to be alone with the thought that they might live to be old.

What happens when a war ends? The movies cut to embraces and parades, to Times Square and kisses and ticker tape, and those are true too. But endings are also messy. Demobilization is a poem written in paperwork. Ships must be re-provisioned for peace. Promotions stall; furloughs expand; the mail has to find new towns. PTSD had not yet been named widely, but it had already moved in with many men and women, unpacking in their dreams, rearranging their breaths. On the Missouri, some sailors celebrated, some stared at the horizon, some wrote letters with hands that could not decide on a script—half block print, half cursive. “It’s over,” they wrote, then “I think,” then “No, really, it is.” But they would not fully believe until they were on a train that took them somewhere their mother recognized.

There’s a reason the world chose a battlewagon for the ceremony. The Missouri was more than steel; she was a symbol of industrial resolve, of a nation that had learned how to turn mines into hull plates and barns into airfields. But aboard that emblem of force, the instrument of peace was gentle: paper and ink and courtesy titles. That juxtaposition is worth keeping. Victory required ships and planes and islands measured by the yard; peace required chairs and pens and the patience to read out names. The future would depend on remembering both halves of the recipe.

Aboard another ship in the bay, a young photographer named Ruth adjusted her shutter speed and tried not to think about the photograph she didn’t take two years earlier because her hands had been too cold. She captured the moment when MacArthur stepped aside and Nimitz leaned in. When she developed the negative later, she saw the slight tremor at the corner of Nimitz’s mouth—a almost-smile—and understood something she hadn’t known: command is a burden you only set down in public after you have learned how to set it down in private. She kept that contact print in a drawer until she died. Her granddaughter would find it and think, “Every ending is also someone’s beginning.”

The symbolism piled up on Missouri’s deck like folded flags. Perry’s 31-star flag, brought out of the Naval Academy museum for the day, reminded everyone that Japan’s opening to the West had begun under canvas and steam and would now be reimagined under airplanes and treaties. The two copies of the instrument—one for the Allies, one for Japan—stared at each other across the table like mirror images that had finally agreed to match. Even the teak planks mattered; wood is an honest material, warm under boots, a reminder that ships are built by hands even when they are designed by equations.

We sometimes tell the story of V-J Day as a neat ending, a clean cut that frees the future from the snag of conflict. That’s tidy, and honesty has no patience for tidy. The war’s consequences spilled forward: occupation, trials at Tokyo, the new constitution in Japan, the rebuilding of cities in ashes, the long argument with the atom that would define geopolitics for the rest of the century. But “ending” doesn’t mean “erase.” It means we choose the tools of repair over the tools of ruin. In that sense, September 2, 1945 was less a full stop than a turn of the page. The story went on, but the genre changed.

Humanize the moment and you will never lose it. Picture Shigemitsu’s careful handwriting, the slight lean of his body that told a private truth about pain. Picture MacArthur removing his sunglasses before he spoke, because naked eyes make promises stronger. Picture a seaman apprentice named Ortiz, who had lied about his age to enlist, quietly palming a tiny chip of teak from a seam near the table—a pocket-sized relic he would carry for six decades, rubbing it between thumb and forefinger on particularly bad nights. Picture a Japanese interpreter who had studied English with a missionary in Nagasaki and now found himself translating his nation’s surrender; when he reached the phrase “We hereby undertake, for the Emperor, the Japanese Government, and their successors, to carry out the provisions,” his voice did not break. He would remember that steadiness for the rest of his life like a borrowed coat.

Ask ten veterans where the war ended and you’ll get eleven answers. Some will say it ended the first time they slept without boots. Others will say it hasn’t ended yet—not for them—because ending is a geography, not a calendar. But when the Missouri’s whistle blew and the documents were carried below, a particular kind of silence fell over the water. It was not the silence of emptiness; it was the silence of possibility. The fleet could leave. The boys could become men in the way that does not require gunpowder. The Pacific could return to being an ocean rather than a map of objectives.

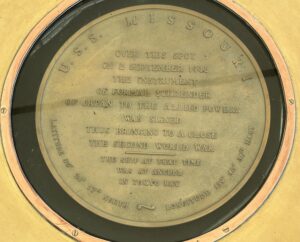

The last words of that ceremony were not etched in marble. They were practical: orders to weigh anchor, to ferry delegations back, to secure the table. A petty officer put the inkstands in a box. A sailor reclaimed the folding chairs from the edge of the stage. Another coiled a length of rope the way his grandfather had taught him, neat and flat, looping the future onto the present. The Missouri would carry many things in her long life—missiles later, tours for schoolkids later still—but she would always carry that hour. Visitors would walk her deck and touch the brass plaque that marks the spot where the table sat and feel taller without understanding why. They would read the names and find their own family names hidden between the lines, because every generation inherits the debts and credits of those signatures.

If you squint, you can see the ceremony backwards: the Allied representatives walking to their places in reverse, the Japanese delegation stepping backward up the brow, the sailors un-saluting, the documents returning to blank paper. It’s a parlor trick, but it makes a point. War is easy to run forward and impossible to rewind. Peace is the opposite: hard to start, easier—if we’re relentless— to keep moving. The Missouri’s deck teaches that paradox perfectly. Starting peace required thousands of days of war plus one hour of ink. Keeping peace would require the next seventy-plus years of discipline, restraint, cooperation, argument, and the dull, gorgeous labor of diplomacy.

Titles like “V-J Day” can become marble if we’re not careful, a crisp acronym that hides the heat of human breath. Bring back the heat. Bring back the sailor whose hands shook. Bring back Shigemitsu’s cane, the soft thud as it touched the deck. Bring back the smell of oil and salt and paper. Bring back Cosgrave leaning to sign and placing his name on the wrong line because injuries do not keep other appointments. Bring back the way a thousand men heard the same words and assigned them a thousand private meanings. And then carry those details with you the next time the world invites you to choose between pride and pragmatism. Remember how ink outperformed steel that morning.

“Where were you when it ended?” It’s a question grandchildren love to ask because endings make good stories. The answers from that day unfurl: a nurse on a hospital ship finally sat down and cried into her hands; a submariner in drydock in Pearl Harbor looked at a patch of blue and thought it had never been so blue; a Marine in Tientsin found a bakery and bought bread even though he didn’t speak the price; a Japanese mother in Yokohama tied back her hair and told her son that the world would be different now, and she meant it as a promise, not a threat. The Missouri’s deck collected those answers the way tree rings collect rain.

“Never again” is an aspiration, not a spell. It doesn’t work on its own. It needs practice, rehearsal, patience—exactly the opposite of how wars start. But aspirations require anchors, and Tokyo Bay on September 2 is one. When we point to that morning, we’re not just remembering relief; we’re remembering a set of choices: surrender rather than annihilation, law rather than vengeance, reconstruction rather than humiliation. The choices were not perfect. They never are. But compared to the alternatives, they shine like a wet deck under soft cloud.

It is tempting to imagine that if you had been there, you would have understood instantly the scale of the moment. Maybe you would have. More likely, you would have looked for your friends in the ranks, checked the line for the mail buoy, wondered about lunch, planned to write home, and then—only later, perhaps years later—understood that you had stood fifteen feet from the hinge on which a century swung. That’s okay. History is kind to late realizations. It stores them for you until you’re ready, then presents them like a photograph you forgot you took.

When the fleet finally dispersed, the bay resumed being water instead of witness. Gulls reclaimed their airspace. The mountains watched with the patience of stone. On the Missouri, the green felt was folded, the table returned to ordinariness, the scuffed mark of a chair leg polished away. But the ship kept the echo. If you stand there today, above that brass plaque, you can hear it if the wind is right: paper sliding across wood, a pen finding its cadence, a signature completing the loop. It sounds like a door unlocking.

And that is the music of endings we should learn to recognize: not brass bands and flyovers—though those are glorious in their moment—but the smaller sounds of human agreement. Pens, breath, chairs, footsteps, a low voice reading names. We learned that music in Tokyo Bay. We can play it again, whenever we need to, if we keep the instruments tuned.