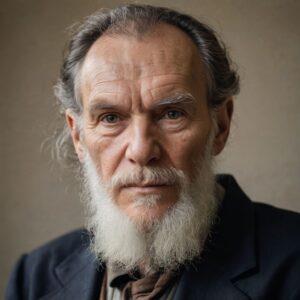

Leo Tolstoy’s face keeps popping up in my mind, a constant presence in the crowded landscape of writers I’ve read and admired. At first glance, he seems an imposing figure – tall, brooding, with a philosophical intensity that makes me feel like I’m staring into the depths of the Russian soul. But as I delve deeper into his work and life, I find myself stuck on one particular aspect: his obsession with finding meaning.

It’s not just that Tolstoy was consumed by existential questions – who isn’t, right? – but how he went about seeking answers. His novels are a sprawling, messy attempt to pin down the elusive truth, like trying to grasp a handful of sand. I’ve spent countless hours getting lost in the complexities of Anna Karenina or War and Peace, watching as characters grapple with their own purpose, only to have it slip through their fingers like grains of sand.

What draws me to Tolstoy’s struggles is how relatable they are. As someone who’s always felt a sense of disconnection from the world around me – a perpetual outsider looking in – I recognize the hunger for meaning that drives him. We both seem to be searching for something more, some underlying pattern or purpose that will make sense of our lives. But while Tolstoy’s search is often grand and public – he writes novels about it, after all! – mine is more private, a nagging feeling that I’m drifting through the world without direction.

This similarity in our existential angst creates a strange kind of intimacy with Tolstoy. It’s as if we’re two people lost in the same wilderness, stumbling towards the same unknown destination. When he writes about the futility of seeking happiness or the inevitability of suffering, I feel like I’m reading my own thoughts back to me.

One aspect that puzzles me is how Tolstoy’s search for meaning seemed to ebb and flow throughout his life. There are moments when he appears almost manic in his pursuit – he’s writing novels about peasants, questioning the value of wealth and power, railing against the Church. But then there are periods of quiet contemplation, when it seems like he’s given up on finding answers altogether.

I find myself wondering if this seesawing between optimism and despair is something I’m familiar with too. As someone who’s struggled to commit to a single path or passion, I’ve often felt like I’m oscillating between two extremes: the thrill of possibility versus the crushing weight of uncertainty. Tolstoy’s ups and downs make me realize that I’m not alone in this struggle – maybe it’s even a necessary part of growing up.

As I continue to grapple with Tolstoy’s ideas, I start to notice something else: how he seems to be searching for meaning within himself, rather than external validation or recognition. This self-reflection is both beautiful and terrifying – beautiful because it shows that even someone as esteemed as Tolstoy struggled with the same doubts and fears as me; terrifying because it makes me wonder if I’m doing the same.

In many ways, Tolstoy’s story feels like a cautionary tale about the dangers of seeking meaning outside ourselves. He devotes his life to creating art, only to become increasingly disillusioned with its power to capture reality. It’s as if he’s trying to find answers in the wrong places – in the grand narratives of history or the platitudes of philosophy – when all along, they’re hidden within himself.

I’m not sure what this says about my own search for meaning. Part of me wants to follow Tolstoy’s example, pouring myself into creative pursuits in hopes that I’ll stumble upon some deeper truth. But another part is terrified by the prospect of becoming so lost in my own introspection that I forget how to engage with the world around me.

As I look back at Tolstoy’s life and work, I realize that his search for meaning has become mine too – a constant companion on this winding journey through adulthood. Maybe it’s not about finding answers or resolving our existential crises; maybe it’s just about showing up, day after day, to the uncertainty and complexity of being human.

The more I reflect on Tolstoy’s search for meaning, the more I’m struck by how it echoes my own struggles with identity. Like him, I’ve felt a deep sense of disconnection from the world around me – not just as an outsider looking in, but also as someone trying to figure out who I am and what I want to be. It’s as if I’m perpetually caught between multiple selves: the academic self that thrives on intellectual pursuits; the creative self that yearns for artistic expression; and the practical self that needs to pay bills and adult like a “real” person.

Tolstoy’s struggles with his own identity are no less complex. He was born into a wealthy family, but felt stifled by the expectations placed upon him. He then rejected his aristocratic upbringing in favor of a life of simplicity and introspection, only to feel torn between his commitment to spirituality and his attachment to material comforts. I wonder if this sense of dissonance is what fuels my own restlessness – the feeling that I’m caught between different versions of myself, none of which quite align with who I truly am.

One aspect of Tolstoy’s life that resonates deeply with me is his rejection of external validation. He became increasingly disillusioned with the fame and recognition he received for his writing, seeing it as a hollow substitute for true meaning. This sense of disillusionment is something I’ve struggled with too – the feeling that success or achievement isn’t enough to fulfill me, that there’s always more to be desired.

It’s interesting to note how Tolstoy’s rejection of external validation led him to focus on his own inner life. He began to write about the peasants and simple folk he encountered during his travels, seeking to capture their wisdom and authenticity in his work. I’m drawn to this aspect of his writing – the way he honors the quiet, everyday moments that often go unnoticed.

As I continue to explore Tolstoy’s life and work, I find myself wondering what it means to truly “show up” in the world – not just as a writer or an artist, but as a human being. It seems like Tolstoy was always searching for ways to do this, whether through his writing, his spiritual practices, or simply by engaging with the people and places around him.

For me, showing up means acknowledging my own limitations and uncertainties. It means recognizing that I don’t have all the answers, and that it’s okay to not know what comes next. Maybe Tolstoy’s search for meaning wasn’t about finding some ultimate truth, but about embracing the complexity and ambiguity of life – and in doing so, discovering a deeper sense of purpose and connection.

I think one of the most striking aspects of Tolstoy’s life is his paradoxical relationship with simplicity. On the one hand, he advocates for a simple, rustic way of living – rejecting the trappings of wealth and status in favor of a more authentic existence. But on the other hand, he’s drawn to grand, epic stories that explore the complexities of human experience.

As someone who’s always been torn between seeking simplicity and indulging in complexity, I find this contradiction fascinating. Sometimes I feel like I’m caught between two opposing desires: the need for clarity and order, versus the thrill of exploration and discovery. Tolstoy’s work often embodies both of these impulses – he seeks to capture the intricate web of human emotions and experiences, even as he advocates for a more straightforward, uncomplicated way of living.

I wonder if this tension between simplicity and complexity is what drives my own creative pursuits. As a writer, I’m drawn to exploring complex themes and ideas, but at the same time, I crave the clarity and focus that comes with simplifying them down to their essence. Maybe Tolstoy’s work is a reminder that these opposing forces are not mutually exclusive – that simplicity can be found in complexity, and vice versa.

Another aspect of Tolstoy’s life that resonates with me is his emphasis on living in the present moment. He writes about the importance of being fully engaged with one’s surroundings, of letting go of distractions and expectations to simply experience life as it unfolds. This idea speaks directly to my own struggles with anxiety and disconnection.

As someone who’s often felt like they’re stuck in their head, lost in thoughts and worries about the future or past, Tolstoy’s message is a powerful one: that true meaning can be found only in the present moment. It’s as if he’s saying, “Stop worrying about what’s coming next – or what’s already passed. Just show up, fully and completely, to this moment right now.”

For me, embracing this idea has been a slow process. I still catch myself getting caught up in worries about the future or regrets about the past. But Tolstoy’s words have helped me begin to see that these distractions are just that – distractions from the beauty and wonder of the present moment.

I’m not sure what this means for my own life, but I do know that it’s something I want to explore further. Maybe Tolstoy’s emphasis on living in the present is a reminder that true meaning isn’t found in some distant future or external validation – but in the simple, everyday moments of connection and awareness.

As I continue to reflect on Tolstoy’s life and work, I’m struck by how his ideas have become intertwined with my own. It’s as if we’re two people lost in the same wilderness, searching for meaning and purpose together. And yet, despite our shared struggles and doubts, Tolstoy’s story feels like a beacon of hope – a reminder that even in the midst of uncertainty, there is always the possibility for growth, transformation, and connection.

I think this is what I love most about Tolstoy’s work: not just his ideas or his stories, but the way he embodies the very qualities he writes about. He’s a flawed, imperfect human being – just like me – struggling to make sense of the world around him. And it’s in these imperfections that I see a reflection of my own struggles, my own doubts and fears.

Maybe Tolstoy’s search for meaning isn’t something we can ever truly complete or resolve. Maybe it’s an ongoing journey, one that requires us to show up to the present moment with humility, openness, and a willingness to learn.

As I reflect on Tolstoy’s imperfections and my own struggles, I’m struck by how his work can be both incredibly optimistic and deeply pessimistic at the same time. On one hand, he writes about the possibility of spiritual awakening, about the potential for human beings to transcend their limitations and connect with something greater than themselves. But on the other hand, he also acknowledges the inevitability of suffering, the futility of seeking happiness in a world that is inherently uncertain.

I think this paradox is what makes Tolstoy’s work so hauntingly familiar to me. As someone who has struggled with anxiety and depression, I know firsthand how easy it can be to get caught up in the pessimistic view – the idea that life is ultimately meaningless, or that we’re all just stuck in some kind of existential quicksand.

But Tolstoy’s optimism is a powerful counterbalance to this despair. He reminds me that even in the midst of suffering, there is always the possibility for growth, transformation, and connection. And it’s this sense of hope that I think is at the heart of his work – not some grand, cosmic solution to our existential problems, but rather a simple, everyday recognition that we are all in this together.

As I continue to explore Tolstoy’s ideas, I’m struck by how they speak directly to my own experiences as a creative person. I’ve always struggled with the idea of “finding my voice” or “discovering my purpose,” feeling like I’m stuck between multiple identities and interests. But Tolstoy’s emphasis on living in the present moment reminds me that maybe this search for identity is just an illusion – that true creativity and meaning come from embracing our imperfections, rather than trying to pin ourselves down into some kind of fixed category.

I think this is what I love most about Tolstoy’s writing: its messy, imperfect quality. He’s not afraid to show us the cracks in his own armor, the doubts and fears that creep in when he’s trying to write about something bigger than himself. And it’s in these imperfections that I see a reflection of my own struggles – the times when I feel like I’m stuck between multiple selves, or when I’m unsure what kind of writer I want to be.

One aspect of Tolstoy’s work that I’ve always found fascinating is his use of irony and humor. He has this wicked sense of humor that catches me off guard every time – a way of poking fun at the pretensions and hypocrisies of society, while also acknowledging our own complicity in these flaws.

I think this use of irony is something I want to explore more in my own writing. As someone who’s always been drawn to satire and social commentary, I’ve often found myself getting caught up in the seriousness of it all – trying to make grand statements about the world, rather than simply observing its absurdities with a twinkle in my eye.

Tolstoy’s example shows me that maybe this is where the real power lies: not in some grand, cosmic statement, but in the simple, everyday observations that catch us off guard. His writing is full of moments like these – little epiphanies or insights that come from his own experiences as a human being, rather than some abstract notion of truth.

As I look back on my reflections about Tolstoy’s life and work, I realize that they’ve become a kind of meditation for me. Not just a intellectual exercise, but a way of exploring my own thoughts and feelings about existence, creativity, and purpose.

I think this is what Tolstoy would want me to remember: that his search for meaning wasn’t just about finding answers or resolving our existential crises – but about embracing the complexity and ambiguity of life itself. And it’s in this messy, imperfect quality that I see a reflection of my own struggles, my own doubts and fears.

Maybe that’s what I love most about Tolstoy’s work: its ability to reflect back at me my own imperfections, my own uncertainties. It’s as if he’s saying, “I see you, Penelope – with all your flaws and contradictions.” And in this recognition, I find a strange kind of comfort, a sense that maybe we’re not so different after all.