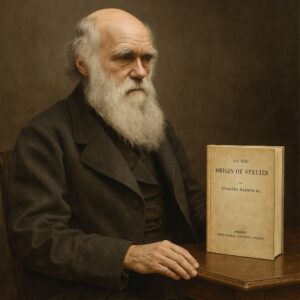

When Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species on November 24, 1859, he did far more than release a scientific book—he detonated an intellectual earthquake whose aftershocks continue to shape every corner of modern thought. It is difficult today, in a world where evolution is a familiar concept taught in classrooms and taken for granted in scientific circles, to fully grasp just how radical, how shocking, and how world-altering Darwin’s ideas were. To Victorian society, the book posed questions that cut to the heart of identity, morality, faith, and humanity’s place in the cosmos. But before it became a flashpoint for controversy and transformation, it was simply the culmination of a deeply personal, decades-long journey of doubt, curiosity, and relentless observation. The publication date is famous now, but the story behind it is even more fascinating—an interplay of private struggle, scientific bravery, and the quiet determination of a man who never saw himself as a revolutionary, yet became one almost by accident.

The seeds of Darwin’s great work were planted long before he ever put pen to paper. As a young man, Charles Darwin was not the stereotype of a bold explorer or a defiant intellectual. He was, by his own admission, shy, deeply sensitive, prone to illness, and searching for direction. Early attempts to mold him into a doctor or a clergyman failed—not because he lacked intelligence, but because his heart simply wasn’t in it. What captivated him instead were beetles, birds, rocks, fossils, and all the small wonders of the living world. He collected specimens like treasure, examined them with intense fascination, and found joy in cataloging the intricate details of nature. It was this quiet passion—not a desire for fame—that eventually placed him aboard HMS Beagle, the ship that would change everything.

The Beagle voyage from 1831 to 1836 exposed Darwin to landscapes and creatures that seemed, to his young and curious mind, almost impossibly varied. Giant tortoises lumbered across volcanic terrain in the Galápagos. Fossilized bones of long-dead giants emerged from Patagonian cliffs. Birds that appeared similar at a distance revealed astonishing variations upon closer inspection. Many of these observations were small—notes in a journal, sketches in a notebook—but for Darwin, they stirred questions that refused to be quieted. Why did species vary so drastically from one island to another? Why did fossils resemble living creatures yet differ in fundamental ways? Why did nature seem to produce endless, subtle variations, almost as if it were experimenting?

These questions did not lead him immediately to a grand theory. Instead, they simmered. Darwin returned to England and began the slow, meticulous work of cataloging his findings. His life settled into a pattern of quiet scholarship—marriage, children, experiments in his home gardens, endless correspondence with naturalists across Europe. Yet beneath the surface of this routine life, a storm brewed. As he reviewed the specimens and notes from the Beagle, patterns began to form. Nature was not static. Species were not fixed. Everything seemed to point toward the same unsettling idea: living things changed over time. Gradually. Relentlessly. According to laws and pressures that played out over millions of years.

For Darwin, this realization was thrilling—and terrifying. He knew that if he could see the implications, the world would eventually see them too, and the consequences would shake the foundations of science, religion, and culture. He moved deliberately, almost cautiously, developing his theory of natural selection not in bursts of inspiration but through steady, painstaking reasoning. To find evidence, he became a kind of scientific detective. He bred pigeons to understand variation. He studied barnacles for eight exhausting years, gaining insights into subtle differences between species. He cataloged plants, insects, and animals from every source available. All the while, he wrote notes—pages upon pages of them—slowly crafting the skeleton of a theory so bold it felt almost dangerous.

And he was right to be wary. Victorian society held tightly to the belief that species were fixed creations, designed individually and perfectly. The idea that humans shared ancestry with other animals was not just unflattering; it was unacceptable. Darwin feared backlash, not only from the church but from his colleagues, his family, and the public. Unlike many scientists hungry for recognition, he hesitated to publish, driven more by a desire for truth than by a thirst for fame. He once described the idea of revealing his theory as like “confessing to a murder.”

For more than twenty years, Darwin kept his growing manuscript largely to himself. But everything changed when another naturalist, Alfred Russel Wallace, independently developed a nearly identical theory of evolution. Wallace’s letter to Darwin in 1858 forced a moment of decision: publish now or risk losing the legacy of decades of work. Darwin, ever modest, insisted that Wallace receive full credit, and in a joint presentation at the Linnean Society, both men were acknowledged. But it was Darwin who undertook the monumental task of expanding the theory into a comprehensive book for the public, one that would synthesize all of his evidence, reasoning, and examples into a single, groundbreaking narrative.

When On the Origin of Species finally appeared in print in 1859, the response was immediate and explosive. The first edition sold out in a single day. Scientists were stunned, intrigued, scandalized. Clergy reacted with alarm and hostility. Newspapers published fierce arguments both defending and condemning the book. Darwin himself, too ill to handle the stress, watched the uproar unfold from home, feeling both relieved to have finally spoken his truth and overwhelmed by the shockwave it caused.

The book itself was written not like a manifesto but like a careful, measured conversation. Darwin avoided attacking religion directly, instead presenting his theory with humility and respect for traditional viewpoints while still making a compelling, evidence-driven case. He introduced the concept of natural selection—a simple but powerful mechanism where organisms better adapted to their environment survive and reproduce, passing on favorable traits. Over generations, small advantages accumulate, shaping species. This idea was both elegant and profound. It did not require divine intervention, nor did it rely on random chaos. It described a universe where complexity arose naturally, driven by adaptation and time.

The beauty of Darwin’s argument was not in its shock value but in its clarity. He built his case piece by piece, drawing from pigeons, barnacles, bees, orchids, fossils, and geographical distributions. These were not abstract concepts; they were real, observable patterns anyone willing to look could see. By grounding his ideas in nature itself, Darwin gave readers the tools to independently verify his claims. For many scientists, this was transformative. For others, it was unsettling, even threatening. Yet the genie was out of the bottle, and the world could never return to the comfortable certainty it once had.

What made Darwin’s publication so monumental was not just the scientific theory it introduced but the broader implications it carried. It challenged humanity’s sense of exceptionalism, suggesting that we were part of the natural world, not separate from it. It implied that life was interconnected, fluid, and ever-changing. It encouraged people to see the world as dynamic rather than static, driven by processes rather than miracles. And perhaps most importantly, it introduced a framework for understanding everything from disease and ecosystems to psychology and genetics. Without Darwin, modern biology would be unrecognizable.

Yet the years following publication were not triumphant for Darwin. His health worsened, leaving him bedridden for long stretches. The stress of public scrutiny weighed heavily on him. He watched as friends defended him in heated debates he was too sick to attend. He endured caricatures, mockery, and accusations of heresy. But he also witnessed the slow, undeniable shift in scientific consensus. Even those who disliked the implications of his theory could not ignore its explanatory power. It worked. It matched evidence. It predicted phenomena. It opened doors to fields that would not fully blossom until decades after Darwin’s death.

In time, the shock turned into acceptance. The backlash softened into curiosity. The theory Darwin had feared to release became the foundation of biological science. Today, evolution is not controversial in laboratories or universities. It is the backbone of medicine, ecology, anthropology, genetics, paleontology, and biotechnology. Its fingerprints are everywhere—from how bacteria develop antibiotic resistance to how species adapt to climate change. Darwin’s quiet, careful observations aboard the Beagle now shape global research, conservation efforts, and our understanding of life itself.

But the human side of Darwin’s story is just as important. He was not a firebrand or a provocateur. He was a gentle, thoughtful man who loved his family, nurtured his garden, and filled pages with sketches of worms, plants, and insects. He never saw himself as a revolutionary, yet his work changed the world more than any battle, treaty, or invention of his time. His courage was not loud but steady—a determination to follow truth wherever it led, even when it threatened the foundations of society.

That is perhaps the most lasting legacy of On the Origin of Species. It is not only a scientific milestone but a reminder of what curiosity can achieve. A reminder that great ideas often begin quietly, in notebooks and gardens, in long walks and quiet reflections. A reminder that truth, once understood, has a power all its own—one that can reshape cultures, challenge assumptions, and expand human understanding in ways no one could predict.

On the day Darwin’s book was published, the world did not change all at once. People still woke, ate, worked, prayed, and lived as they always had. But a crack had formed in the old worldview. Light entered through it. Over the years, that crack widened until the entire landscape of science and philosophy shifted. The publication was not the end of a journey but the beginning of one—one that all of humanity is still traveling.

More than a century and a half later, Darwin’s ideas continue to inspire awe. In every forest, every shoreline, every laboratory, the principles he uncovered remain alive. On the Origin of Species is no longer just a book. It is a lens through which we see the living world—a lens that reveals beauty, complexity, struggle, and resilience. It asks us to see life not as fixed and unchanging but as a vast, ongoing story shaped by countless forces over unimaginable spans of time.

And at the heart of that story is a simple truth: everything evolves.

Darwin’s publication was the moment we first understood that truth fully. And from that moment onward, humanity’s understanding of itself, and of the world it inhabits, would never be the same.