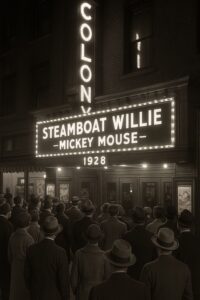

When “Steamboat Willie” premiered at the Colony Theatre in New York City on November 18, 1928, audiences had no idea that they were witnessing the birth of a global icon, the reinvention of animated storytelling, and a pivotal moment in the cultural history of the 20th century. It was just an eight-minute black-and-white cartoon, shown after a live vaudeville act and before a feature film. It was jaunty, lively, and mischievous. It had synchronized sound—something novel at the time, especially in animation—and it starred a small, grinning figure with circular ears, button shorts, and an irresistible swagger. His name, revealed only later in promotional materials, was Mickey Mouse. But that night, he was simply the star of a cartoon that made the audience laugh, clap, and lean forward with a sense of delight that was strangely new.

“Steamboat Willie” was not the first cartoon ever made, nor the first one with sound, nor even the first Mickey Mouse short produced. But it was the first animated film to bring all the elements of sound, rhythm, character personality, humor, and story into a single cohesive artistic experience. Its premiere marked the moment when animated films stopped being novelties for children and became a legitimate form of entertainment for all ages. It transformed Walt Disney from a struggling animator facing bankruptcy into a pioneering filmmaker. It launched a character who would become one of the most recognizable symbols on earth. And, perhaps most profoundly, it rewired the expectations of what animation could be, setting the stage for a global industry that continues to evolve nearly a century later.

To understand the impact of “Steamboat Willie,” one must understand the context in which it appeared. The late 1920s were a period of rapid technological and cultural transformation. The film industry had just experienced the seismic arrival of “The Jazz Singer” in 1927, the first feature film to incorporate synchronized dialogue. Sound cinema—“talkies”—was exploding across the country, transforming the way stories were told and experienced. Silent film stars scrambled to adapt to the new medium. Musicians and sound technicians flocked to Hollywood. Studios invested enormous sums in retrofitting theaters with sound equipment.

But in the world of animation, things were different. Silent cartoons had developed their own rhythm, relying on exaggerated expressions, physical humor, and printed title cards. They were clever, funny, and inventive, but they floated above reality, unanchored by the weight of voice or soundtrack. Synchronizing action with sound was technically daunting. Audiences loved animation, but it was considered a minor art—fun, but limited.

Walt Disney was determined to change that. His studio, founded only a few years earlier, had produced the Oswald the Lucky Rabbit shorts for Universal. Oswald had become popular, and Disney believed the character was the foundation of his company’s future. But in 1928, Disney suffered a crushing betrayal when Universal and animator Charles Mintz cut him out of the deal, seized the rights to Oswald, and hired away most of his animation staff. Disney, stunned and humiliated, returned to Los Angeles with no character, no team, and almost no options.

Yet failure did something remarkable: it sharpened his determination. On the train ride home, Disney scribbled ideas, searching for a new character who would surpass Oswald. After experimenting with sketches, he refined a design he had created earlier—originally inspired, according to legend, by a tame mouse he once kept as a pet in his Kansas City studio. It was simple enough for quick animation, expressive enough for visual storytelling, and cute enough to appeal to wide audiences. This was the birth of Mickey Mouse. Disney, with the help of his loyal animator Ub Iwerks—whose technical skill bordered on the superhuman—began producing test animations.

Two Mickey Mouse cartoons, “Plane Crazy” and “The Gallopin’ Gaucho,” were completed first, but they were silent shorts and failed to find a distributor. Sound was clearly the future. Disney, always visionary, made the bold decision to reimagine his third Mickey Mouse short as a fully synchronized sound cartoon. He invested nearly everything the studio had. He and his small team worked relentlessly to match sound to action, a process that involved meticulous timing, dozens of retakes, and the invention of new animation techniques.

The result was “Steamboat Willie,” a parody of Buster Keaton’s popular 1928 film “Steamboat Bill, Jr.” The cartoon opens with Mickey at the wheel of a steam-powered riverboat, whistling a jaunty tune as he bounces in place—a moment so iconic that it remains the logo animation for Walt Disney Animation Studios to this day. Minnie Mouse makes an appearance as a passenger, and Mickey, attempting to impress her, uses the boat’s livestock as improvised musical instruments. The short is a delightful mix of slapstick, music, and personality-driven humor. Mickey is mischievous, energetic, and expressive. He laughs, struggles, improvises, and performs. He interacts with the world around him not as a flat symbol, but as a character with spirit.

When the cartoon premiered, the audience reaction was electric. People had never seen anything like it. The synchronization—every whistle, tap, bounce, and bleat—felt alive. It was as if the animated world had suddenly gained a heartbeat. For the first time, an animated character seemed to occupy the same sensory space as the viewer. Mickey Mouse did not simply move; he performed. He was not just a drawing; he was an entertainer. And the crowd fell in love immediately.

New York critics hailed the cartoon as a breakthrough. Trade publications praised its innovation. Word of mouth spread. Within months, “Steamboat Willie” was being screened across the country, drawing enormous attention. Walt Disney, once on the brink of failure, now found himself at the forefront of a new era in animation.

The success of “Steamboat Willie” transformed the Disney studio. It brought revenue, recognition, and a wave of new opportunities. Disney and Iwerks quickly added synchronized sound to the earlier Mickey films, re-releasing them to eager audiences. They produced new shorts featuring Mickey and other characters, each one more sophisticated than the last. The Disney brand grew rapidly, and Mickey became a cultural phenomenon—appearing on merchandise, in newspapers, and in conversations at dinner tables across America.

But perhaps the most important legacy of “Steamboat Willie” is the way it redefined animation itself. Before this film, animation was seen primarily as gag-driven entertainment. After it, studios recognized animation as a legitimate form of cinematic expression. The use of music became central to animated storytelling. The concept of timing—of choreography between movement and sound—became foundational. The emotional range of animated characters expanded, paving the way for richer stories, deeper themes, and more ambitious artistic experimentation.

Walt Disney, always pushing the boundaries, used the momentum from “Steamboat Willie” to pursue bigger dreams. Within a decade, he released “Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs,” the world’s first full-length animated feature—a film many thought would be a financial catastrophe but instead became one of the greatest triumphs in cinematic history. The DNA of that success can be traced back to the mouse who whistled on a steamboat.

Yet the significance of “Steamboat Willie” extends beyond the animation industry. It coincided with a broader cultural shift in America. The late 1920s were the twilight of the Roaring Twenties, a period of booming economy, jazz music, social change, and technological innovation. The nation was on the cusp of the Great Depression, though few realized it. “Steamboat Willie,” with its energy and optimism, captured the spirit of a society both confident and restless. It was lighthearted, dynamic, and full of laughter—qualities people desperately needed as the world grew uncertain.

The character of Mickey Mouse, shaped by the cartoon’s success, became a symbol not just of entertainment but of resilience. Born from Walt Disney’s greatest professional setback, Mickey was proof that creativity could overcome failure. He represented joy, perseverance, and possibility. Over the decades, Mickey would evolve, gaining a cleaner personality and a more polished design, but the mischievous spark that made him compelling in “Steamboat Willie” never disappeared.

For audiences today, “Steamboat Willie” might seem simple, modest, even quaint. But its charm endures precisely because it is a snapshot of a revolutionary moment—a moment when sound met line, when imagination met innovation, and a new vocabulary for storytelling was born. Watching it now is like opening a time capsule that contains not only humor and music, but the seeds of nearly every animated film that followed.

The cartoon’s public domain status as of 2024 has renewed interest in its historical importance, prompting new discussions about copyright, creativity, and the legacy of early animation. Yet regardless of legal status, its cultural value stands unchanged: “Steamboat Willie” is a cornerstone of cinematic history, a foundational work that changed the trajectory of an entire artistic medium.

For Walt Disney personally, the success of “Steamboat Willie” validated his belief in storytelling through animation. It gave him the confidence—and the resources—to dream bigger. Every project he pursued afterward, from theme parks to television to full-length animated films, carried echoes of that first triumph. The steamboat’s whistle was not just a sound effect; it was the starting note of a symphony that would play across the 20th century and beyond.

And for audiences around the world, “Steamboat Willie” remains a reminder of the magic that happens when creativity and technology meet. It embodies the beauty of simplicity, the power of innovation, and the universal human love of laughter. More than that, it captures a defining moment when the world discovered that drawings could sing, dance, and feel alive—and that imagination could become a living presence on the screen.

Nearly a century later, the little black-and-white cartoon still hums with energy. It still sparkles with humor. And the mouse who began as a scrappy underdog still stands tall as a symbol of joy, resilience, and artistic wonder. “Steamboat Willie” did more than launch a character; it launched a revolution. And it did so with nothing more than eight minutes of ink, sound, rhythm, and heart.

It is a testament to the idea that small beginnings can change the world—not with thunder, but with a whistle.