It was on December 30, 2006, that the world witnessed the execution of one of its most infamous figures – Saddam Hussein. The former Iraqi dictator had been in American custody since his capture in a hiding spot north of Baghdad on December 13, 2003. His death marked the end of an era, not just for Iraq but also for the global community that watched with bated breath as he stood trial and awaited his fate.

Saddam’s rise to power began in the early 1970s when he seized control from President Abd al-Karim Qasim following a bloody coup. He ruled with an iron fist, suppressing dissent and opposition through brutal means. His regime was characterized by human rights abuses, economic mismanagement, and aggressive military expansion. The Iran-Iraq War of the 1980s left deep scars on Iraq’s economy and its people, but it also solidified Saddam’s grip on power.

The invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 marked a turning point for Saddam and his regime. While initially successful, the subsequent Allied intervention forced him to withdraw from Kuwait, leaving behind a trail of destruction and chaos. The aftermath saw widespread international sanctions imposed on Iraq, exacerbating its economic woes and leaving millions without access to basic necessities.

The no-fly zones established by the United States and the United Kingdom over northern and southern Iraq were another direct consequence of Saddam’s actions. These zones allowed the Allies to maintain control while creating an environment that fueled resentment among Iraqis who felt they had been denied their sovereignty. The period also saw a shift in Saddam’s domestic policies as he turned towards radical Islamism, cultivating ties with terrorist groups such as Al-Qaeda.

The 2003 invasion of Iraq by American and British forces brought about the downfall of Saddam’s regime. After an initial resistance, his loyalist forces collapsed, and on April 9, 2003, Baghdad fell to coalition troops. As Iraqi cities celebrated their newfound freedom, many also mourned the loss of a leader who had become synonymous with national pride.

Saddam’s trial began in October 2005, over two years after his capture. Accused of ordering the execution of 148 Shi’ites from Dujail following an assassination attempt against him in 1982, Saddam stood before the Iraqi High Tribunal (IHT) to face justice. His defense team argued that he had been unfairly targeted and that the trial was a sham, while others saw it as a long-overdue reckoning for his crimes.

The verdict on November 5, 2006, was unanimous: death by hanging for Saddam. While some Iraqis welcomed this outcome, others feared it would exacerbate sectarian tensions between Shi’ites and Sunnis. This anxiety proved well-founded as thousands of protesters took to the streets, not in celebration but in opposition to what many saw as a miscarriage of justice.

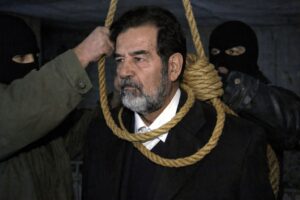

Saddam’s execution on December 30, 2006, was carried out at Kadhimiya prison, just north of Baghdad. In the hours leading up to it, his lawyer made an eleventh-hour appeal to spare his client’s life. Saddam himself remained defiant until the very end, maintaining that he had done nothing wrong and refusing even to acknowledge the legitimacy of the trial.

In a bizarre twist, Saddam requested that his family be allowed to identify him after his execution, fearing that his body might be claimed by another person or that it would not be recognized. This request was met with skepticism by those present but highlights the deep paranoia that had characterized his regime and continues to influence Iraqi politics today.

As news of Saddam’s death spread around the world, reactions were mixed. Some hailed it as a triumph for justice and a fitting end to a brutal dictator, while others saw it as an opportunistic move by American forces seeking to consolidate their power in Iraq. In Iraq itself, the mood was tense, with fears that the execution would create a power vacuum or fuel further instability.

The months following Saddam’s death were marked by violence and uncertainty as factions vied for control of the country. Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), which had previously been weakened by the invasion, began to regroup and wreak havoc across the nation. As one faction after another fell, it became clear that the removal of Saddam was only a small step towards stability.

The execution also sparked debate about the role of international law in the post-Saddam era. Critics accused the Bush administration of attempting to sidestep due process and ignore human rights norms by pushing for capital punishment without allowing for appeals or alternatives. The use of such extreme measures, they argued, undermined efforts to rebuild Iraq’s fragile institutions.

On a broader level, Saddam’s trial and execution have been seen as part of a larger conversation about the relationship between justice and politics in modern warfare. In the years following 9/11, governments around the world faced unprecedented challenges in balancing security concerns with human rights obligations. As in Iraq, many countries struggled to reconcile their pursuit of accountability for past atrocities with the imperatives of national sovereignty.

In conclusion, Saddam Hussein’s execution marked a watershed moment in international relations and domestic Iraqi politics. While it brought some measure of closure for victims of his regime, it also highlighted the complexities and challenges inherent in transitioning from dictatorship to democracy.

The years leading up to Saddam’s execution were marked by a series of tumultuous events that would shape the fate of Iraq and its people for generations to come. The invasion of Kuwait in August 1990 was a pivotal moment in modern Middle Eastern history, one that would test the mettle of international relations and diplomacy.

As Iraqi forces poured into Kuwait, the United States, under the leadership of President George H.W. Bush, rallied an international coalition to push back against Saddam’s aggression. The subsequent liberation of Kuwait marked a rare instance of successful multilateral cooperation in modern times, with over 40 nations contributing troops to the effort.

However, the aftermath of Operation Desert Storm was marred by controversy and recrimination. The Gulf War, as it came to be known, saw a series of devastating airstrikes against Iraqi military targets, including the infamous bombing of Baghdad’s infrastructure. While these actions were intended to weaken Saddam’s regime, they also had the unintended consequence of creating widespread suffering among ordinary Iraqis.

The no-fly zones established by the United States and its allies over northern and southern Iraq further complicated an already volatile situation. The zones, designed to prevent Iraqi aircraft from attacking Kurdish populations in the north and Shi’ite rebels in the south, became a constant source of tension between Baghdad and Washington.

Saddam, emboldened by the weakness of his opponents, began to exploit these divisions for his own gain. He cultivated ties with extremist groups like Al-Qaeda, fueling a radicalization of his regime that would have far-reaching consequences for Iraq and the wider region.

The 2003 invasion of Iraq by American and British forces brought an end to Saddam’s rule, but it also opened up a Pandora’s box of sectarian violence and instability. As the coalition struggled to establish order in Baghdad, it became clear that the removal of Saddam was only the first step towards a more profound transformation of Iraqi society.

The aftermath of the invasion saw a rise in tensions between Shi’ite and Sunni populations, as well as an increase in violence perpetrated by extremist groups like Al-Qaeda. The fragile balance between these competing forces would be tested to its limits in the years that followed, with far-reaching implications for regional stability and global security.

Saddam’s trial began in October 2005, over two years after his capture. Accused of ordering the execution of 148 Shi’ites from Dujail following an assassination attempt against him in 1982, Saddam stood before the Iraqi High Tribunal (IHT) to face justice. His defense team argued that he had been unfairly targeted and that the trial was a sham, while others saw it as a long-overdue reckoning for his crimes.

The verdict on November 5, 2006, was unanimous: death by hanging for Saddam. While some Iraqis welcomed this outcome, others feared it would exacerbate sectarian tensions between Shi’ites and Sunnis. This anxiety proved well-founded as thousands of protesters took to the streets, not in celebration but in opposition to what many saw as a miscarriage of justice.

The months leading up to Saddam’s execution were marked by a series of last-minute appeals and desperate attempts to save his life. His lawyer, Khalil al-Dulaimi, made an eleventh-hour appeal to spare his client’s life, arguing that the trial had been unfair and that Saddam’s sentence was unwarranted.

Saddam himself remained defiant until the very end, maintaining that he had done nothing wrong and refusing even to acknowledge the legitimacy of the trial. His defiance was a testament to the deep-seated conviction that had driven him throughout his life: that he was the rightful ruler of Iraq, and that any opposition to his rule was illegitimate.

In a bizarre twist, Saddam requested that his family be allowed to identify him after his execution, fearing that his body might be claimed by another person or that it would not be recognized. This request was met with skepticism by those present but highlights the deep paranoia that had characterized his regime and continues to influence Iraqi politics today.

As news of Saddam’s death spread around the world, reactions were mixed. Some hailed it as a triumph for justice and a fitting end to a brutal dictator, while others saw it as an opportunistic move by American forces seeking to consolidate their power in Iraq. In Iraq itself, the mood was tense, with fears that the execution would create a power vacuum or fuel further instability.

The months following Saddam’s death were marked by violence and uncertainty as factions vied for control of the country. Al-Qaeda in Iraq (AQI), which had previously been weakened by the invasion, began to regroup and wreak havoc across the nation. As one faction after another fell, it became clear that the removal of Saddam was only a small step towards stability.

The execution also sparked debate about the role of international law in the post-Saddam era. Critics accused the Bush administration of attempting to sidestep due process and ignore human rights norms by pushing for capital punishment without allowing for appeals or alternatives. The use of such extreme measures, they argued, undermined efforts to rebuild Iraq’s fragile institutions.

On a broader level, Saddam’s trial and execution have been seen as part of a larger conversation about the relationship between justice and politics in modern warfare. In the years following 9/11, governments around the world faced unprecedented challenges in balancing security concerns with human rights obligations. As in Iraq, many countries struggled to reconcile their pursuit of accountability for past atrocities with the imperatives of national sovereignty.

The trial and execution of Saddam Hussein have left a lasting impact on international relations and domestic Iraqi politics. While it brought some measure of closure for victims of his regime, it also highlighted the complexities and challenges inherent in transitioning from dictatorship to democracy.

In the years that followed, Iraq continued to grapple with the legacy of Saddam’s rule. The country struggled to rebuild its institutions, restore its economy, and reconcile its sectarian divisions. The removal of Saddam was only a small step towards this goal, and much work remains to be done if Iraq is to achieve true stability and prosperity.

The trial and execution of Saddam Hussein have also sparked important debates about the role of international law in modern warfare. As nations continue to grapple with the complexities of terrorism, insurgency, and regime change, it is essential that we consider the lessons learned from this critical moment in history.

In 2008, a report by Human Rights Watch noted that “the trial was marred by procedural irregularities and the absence of a fair defense.” The report went on to say that “while the Iraqi High Tribunal (IHT) made some efforts to address these concerns, it failed to fully meet international standards for fairness and impartiality.”

These findings were echoed by other human rights organizations, which argued that the trial had fallen short of its promise to bring accountability to Saddam’s crimes. While some Iraqis saw the trial as a necessary step towards closure, others felt that it was an attempt to sidestep more fundamental questions about the nature of power and accountability in modern societies.

In the years since Saddam’s execution, there has been a growing recognition of the need for greater international cooperation on issues related to human rights and transitional justice. The establishment of institutions like the International Criminal Court (ICC) is a testament to this trend, as is the increasing emphasis on national-level prosecutions of war crimes and atrocities.

However, much work remains to be done if we are to fully realize the potential of these developments. As we continue to navigate the complexities of modern warfare and regime change, it is essential that we prioritize accountability, transparency, and human rights in our pursuit of justice and stability.

In conclusion, Saddam Hussein’s execution marked a watershed moment in international relations and domestic Iraqi politics. While it brought some measure of closure for victims of his regime, it also highlighted the complexities and challenges inherent in transitioning from dictatorship to democracy.

The trial and execution of Saddam Hussein have left a lasting impact on our understanding of justice, power, and accountability in modern warfare. As we reflect on this critical moment in history, it is essential that we continue to grapple with its implications for international relations, human rights, and the pursuit of stability and prosperity around the world.

In doing so, we must not forget the lessons learned from Saddam’s trial: that justice requires a commitment to fairness, transparency, and accountability; that power and politics are inextricably linked with issues related to human rights and transitional justice; and that only through a deep understanding of these complexities can we hope to build more just and peaceful societies for all.

As we move forward into an uncertain future, it is essential that we draw on the wisdom of this critical moment in history. By doing so, we may yet find a way to reconcile our pursuit of justice with the imperatives of national sovereignty, to balance our security concerns with human rights obligations, and to build more just and peaceful societies for all.

The road ahead will be long and difficult, but it is one that we must travel if we hope to create a world where power is exercised in accordance with human rights principles, and where accountability and transparency are the hallmarks of justice.