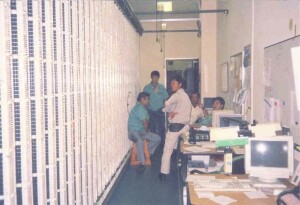

At first glance, the photograph seems simple enough: a group of Okinawan technicians standing proudly in the telephone exchange at Kadena Air Base, with the vast metal skeleton of the main distribution frame stretching behind them like a cathedral of wires. Their posture is relaxed but purposeful, each man aware that the work they do, often invisible to outsiders, keeps the great machinery of a major U.S. Air Force installation running smoothly. On the left of the frame rises the intricate lattice of jumpers, blocks, and copper lines that form the nervous system of the switch, a sight familiar to any communications engineer. But to the untrained eye, it is simply a wall of wires. Hidden behind this frame, and central to their labor, is a piece of equipment that defined an era of military communications: the DMS-100 digital switch. To understand its presence at Kadena is to understand both the story of technology in the late twentieth century and the story of the people—Americans and Okinawans alike—who kept it alive.

The DMS-100 was not just a machine; it was a declaration that the world had entered a new age of connectivity. Built by Northern Telecom (later Nortel), it was one of the most sophisticated digital telephone switching systems of its time. Unlike the clunky electromechanical gear it replaced, with its relays and crossbars clicking endlessly in dusty rooms, the DMS-100 operated with silent precision. It was digital, fast, and flexible, able to handle tens of thousands of lines and trunks, supporting both military circuits and civilian calls. For a base like Kadena, the largest U.S. Air Force installation in the Pacific, it was a revolution. The DMS-100 could seamlessly connect commanders to Washington, families to relatives back home, and airmen to their Okinawan neighbors, all through a web of copper, fiber, and logic spread across racks of cards and frames.

But the machine itself was only half the story. The other half lived in the hands of the Okinawan technicians who worked in that room every day. They were local nationals, hired to provide expertise and continuity in a place where American personnel rotated every few years. They learned the DMS-100’s inner workings with care, mastering the art of tracing faults through miles of jumper wire, swapping out line cards, and maintaining the main distribution frame so that every telephone in the sprawling base had a voice. They were electricians, engineers, troubleshooters, and teachers rolled into one. Their quiet competence was essential: while the airmen came and went, while commanders rose through the ranks and departed, these men stayed. Their presence ensured the switch remained stable, reliable, and ready for anything.

Life in the switch room was a blend of monotony and urgency. On most days, the technicians clipped wires, traced circuits, and updated documentation. The hum of the air conditioning mixed with the occasional crackle of a test set and the faint whiff of solder. But on some days, when storms knocked out lines or when urgent orders demanded new circuits, the pace quickened. Then they moved with the urgency of men who knew that every second mattered, that behind the tangle of wire lay missions, families, and the very reputation of the base. To them, each pair of copper lines carried more than electrons; it carried the lifeblood of communication.

The DMS-100 was a marvel in its time. Using time-division switching, it transformed analog voice signals into digital data, sliced into tiny time slots and switched through memory. This allowed conversations to be routed quickly, efficiently, and with remarkable clarity. Unlike the old analog exchanges, which often introduced noise and distortion, the DMS-100 delivered clean, crisp connections. It could scale easily, too, handling thousands of users while supporting services like voicemail, call forwarding, and conference calls—features that sound trivial now but were transformative in the 1980s and 1990s. For Kadena, with its thousands of personnel and its constant readiness for operations across the Pacific, the DMS-100 was indispensable.

Yet it was not just about the technology. It was about the intersection of cultures inside that switch room. Americans brought the system, trained on it briefly before moving to their next duty station, while Okinawans provided long-term stewardship. These local workers were often bilingual, navigating both technical manuals in English and the daily chatter in Japanese or Okinawan dialects. They embodied the hybrid nature of the base itself: an American outpost embedded in the soil of Okinawa, dependent on the skills and dedication of its host community.

Their work was often invisible to outsiders. When an airman picked up a phone to call home, he rarely thought about the main distribution frame or the men who kept it in order. When a commander patched into a secure conference call with Pacific Command, the thought rarely extended to the Okinawan technician who had tested the circuit that morning. But invisibility did not mean insignificance. These technicians were like the unseen gears of a watch, ensuring that time kept moving, that missions were not delayed, that families could speak across oceans.

The switch itself stood as a monument to the Cold War era. Kadena was a frontline installation, tasked with projecting airpower across the Pacific and standing ready for crises on the Korean Peninsula, in Taiwan, or beyond. Communications were as important as fuel or munitions. A scrambled message, a dropped call, or a failed line could spell disaster in an age where minutes could determine outcomes. The DMS-100 provided reliability and redundancy, with hot-swappable line cards, fault-tolerant design, and constant monitoring. It was a system built for an age of tension, where the flow of information was as strategic as the positioning of bombers on the flight line.

And yet, the photograph captures something more human than technological. The men in the picture are not machines. They are smiling faintly, standing with casual ease, dressed not in uniforms but in the simple clothes of workers who know their craft. They represent continuity, a steadying presence in a base defined by rotation and transience. In their hands, the main distribution frame is not an abstraction; it is a daily reality, a challenge to be met with patience and skill.

Over time, the DMS-100 would be replaced by newer systems. Digital switches gave way to packet-switched networks, to VoIP, to software-defined solutions that run in data centers rather than in rooms filled with copper. But the legacy of the DMS-100 remains, especially in places like Kadena. It represents the bridge between eras: from analog to digital, from isolated switches to global connectivity. And it represents the bridge between peoples: Americans and Okinawans working together, not in the glare of headlines or the roar of jets, but in the quiet hum of a switch room.

To write about a telephone switch is to risk boredom, but to write about the people who kept it alive is to tell a story of resilience and cooperation. The DMS-100 was an engineering marvel, but its real magic lay in the hands of the men who maintained it. They transformed it from a box of circuits into the heartbeat of a community. They ensured that when a young airman called his parents, when a commander briefed Washington, when two friends chatted across base housing, the line was clear. They turned the abstract into the intimate, the global into the personal.

The story of Kadena’s DMS-100 is a reminder that history is not only written in battles or treaties but also in wires and voices, in the invisible labor of those who ensure we can speak to one another. The men in the photograph are not famous, but they are part of the great chain of history, their work woven into the story of a base, a nation, and an alliance that has endured for decades. And though the DMS-100 may now be silent, replaced by newer machines, its legacy endures in the voices it once carried, in the lives it connected, and in the bonds it strengthened.

So the next time one looks at the flight line or the radar domes of Kadena, it is worth remembering the quieter rooms, the telephone switches, the distribution frames, and the technicians who kept them alive. For in those rooms, history was not only observed but enabled, one call at a time.