History doesn’t always announce itself with a thunderclap, but August 1, 1834, and August 1, 1914, were days when the world felt two very different yet equally monumental shifts. One marked the end of institutionalized slavery in much of the British Empire, a culmination of moral reckoning and decades of fierce activism. The other marked the beginning of a mechanized nightmare that would consume an entire generation in blood and steel: Germany’s declaration of war on Russia at the dawn of the First World War. On this single date, eighty years apart, the world experienced both a profound human liberation and the ignition of one of its darkest military catastrophes. To understand August 1 is to recognize the simultaneous potential for human progress and destruction—etched forever into the annals of global memory.

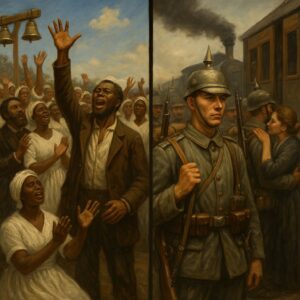

When the sun rose over the British Empire on August 1, 1834, it marked the first day in centuries that slavery was no longer legal in the vast majority of its colonies. The Slavery Abolition Act, passed a year earlier in 1833, officially took effect. For many, particularly in the Caribbean, this date symbolized long-awaited justice, hope, and a new beginning. Yet, the story is not one of immediate freedom or fairness. While the law officially abolished slavery in much of the British Empire—including the West Indies, Canada, and parts of Africa—it did so with constraints that reflect the deep economic and racial biases still embedded in the empire’s institutions. Nearly 800,000 enslaved Africans were “freed,” but many were forced into a system called “apprenticeship,” which effectively prolonged their servitude under a different label.

Still, even with its limitations, the act was revolutionary. It was the result of decades of unrelenting pressure from abolitionists like William Wilberforce, Olaudah Equiano, Thomas Clarkson, and countless others—many of them formerly enslaved or black British citizens who risked their lives and reputations to speak truth to power. The movement had faced fierce opposition from powerful plantation owners and politicians with vested interests in the massive economic engine fueled by slavery. But a combination of moral pressure, public awareness campaigns, and the raw courage of people fighting for their dignity finally won out. The British Parliament, in a moment of moral clarity, enacted the legislation that would ultimately cost the government £20 million—an enormous sum at the time—to compensate slaveowners, not the formerly enslaved, for their “loss of property.”

Across the Caribbean, bells rang, and celebrations erupted at midnight on July 31. On islands like Barbados and Jamaica, formerly enslaved people dressed in white to signify purity and rebirth. Some gathered for religious services that carried into the dawn. But this hope was complicated by the reality that freedom did not equate to equality. Land was scarce, education limited, and racism institutionalized. Still, the symbolic and real power of the law could not be denied. In countless ways, August 1 became not just Emancipation Day, but a rebuke to centuries of cruelty, a crack in the edifice of empire that would continue to crumble over the next century.

Fast forward to August 1, 1914, and the mood in Europe was the opposite of celebratory. The early 20th century had been a time of frenzied nationalism, militarism, and entangled alliances that turned regional tensions into global crises. After the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914, Europe stood on a knife’s edge. A tangle of treaties meant that what should have remained a localized conflict quickly spiraled into something catastrophic.

Germany, aligned with Austria-Hungary, saw Russia’s mobilization in defense of Serbia as a threat that could not be ignored. By August 1, after failed diplomatic maneuvers and ultimatums, Kaiser Wilhelm II signed the order for German mobilization and declared war on Russia. The once-confident empires of Europe were tumbling into a vortex of trench warfare, poison gas, and mass death from which none would emerge unscathed.

The decision was both calculated and terrifying. Germany, sandwiched between France and Russia, had long feared a two-front war. Its leaders believed that by acting quickly—using the Schlieffen Plan—they could defeat France rapidly before Russia could fully mobilize. But war is rarely so neatly executed. Within days, Germany would invade neutral Belgium, prompting Britain to declare war. What was once a Balkan affair became a global inferno. On August 1, as men donned uniforms and families waved their sons off to war, few could imagine the magnitude of the destruction that lay ahead. This wasn’t to be another quick, chivalrous war like those of the 19th century. It would be a mechanized slaughter.

For Germany, August 1 was both a declaration and a death knell. The country’s military machine was unmatched in discipline and organization, but it underestimated the resilience of its enemies and the horrors of trench warfare. The Western Front, stretching from the North Sea to Switzerland, would become a symbol of futility and bloodshed. Millions died in muddy fields over inches of territory. Machine guns, barbed wire, and artillery tore human bodies apart with ruthless efficiency. Entire towns in Belgium and France were flattened. Chemical weapons blinded and suffocated. The war wasn’t just fought on the battlefield—it consumed economies, rewrote borders, and reshaped ideologies.

And while white Europeans clashed in the heart of the continent, they pulled the rest of the world into their war. Colonial troops from India, Africa, the Caribbean, and elsewhere were conscripted or volunteered to fight in a war not of their own making. These soldiers were often treated as second-class—even as they shed blood on foreign soil for imperial masters who denied them basic rights back home. Their participation in WWI is frequently overlooked, but it sowed the seeds for later decolonization movements. Men who had fought and died for Europe returned to their homelands with new ideas about nationalism, freedom, and justice. August 1, 1914, may have sparked war, but it also ignited movements for liberation that would roar louder in the decades that followed.

It’s a strange symmetry that on this same date in different centuries, humanity simultaneously demonstrated its capacity for moral advancement and catastrophic regression. On one hand, the end of slavery in the British Empire was an unprecedented acknowledgment of human rights—imperfect and flawed, yes, but still an irreversible step forward. On the other, the beginning of WWI was a chilling reminder of how quickly diplomacy, decency, and logic can be discarded in the face of pride, nationalism, and fear.

What ties both events together is the human cost and the legacy they left behind. The Slavery Abolition Act didn’t end exploitation. Former slaves faced systemic racism, poverty, and segregation. But it gave future generations a legal foundation upon which to build. Civil rights movements, post-colonial struggles, and modern anti-racist campaigns all trace part of their lineage to that historic law. Similarly, the horrors of WWI paved the way for international cooperation and institutions aimed at preventing such conflicts in the future. The League of Nations may have failed, but it was the precursor to the United Nations. Geneva Conventions were updated. Global diplomacy evolved. The trauma of the war was so profound that many societies reimagined what peace, justice, and cooperation should look like.

These events are also connected by the role of ordinary people. Slavery didn’t end just because politicians woke up with a conscience. It ended because of relentless activism, slave revolts, pamphlets, boycotts, and public pressure. The war, too, wasn’t won solely in war rooms and strategy maps—it was endured by millions of soldiers, nurses, laborers, and citizens who sacrificed more than they could afford. The truest lessons from August 1 come not from kings or kaisers, but from the nameless individuals who fought for something better or bore the burden of decisions made far above their heads.

In some ways, August 1 stands as a reminder of duality: the capability of societies to both uplift and destroy, to grant freedom and to deny it elsewhere, to learn from the past and yet repeat its darkest mistakes. History doesn’t often offer clean narratives. It gives us messiness, contradiction, and complexity. But that’s where its value lies. We study August 1 not to glorify or condemn outright, but to recognize how the forces of change—whether they be abolitionist courage or militaristic aggression—shape the world we inherit.

So when we mark this date, it’s worth pausing to reflect not just on the events themselves but on what they demand of us now. Are we honoring the legacy of those who fought to abolish slavery by confronting modern exploitation? Are we remembering the devastation of war by fostering diplomacy, empathy, and global cooperation? Are we acknowledging that human progress doesn’t follow a straight line, but requires constant vigilance?

The legacies of August 1—freedom from chains, and the descent into war—both echo loudly today. And while we cannot change the past, we can shape the future it leads us toward.