Some dates seem to carry more history than they can hold, as if time itself decided to stack meaning upon meaning until the weight of memory was almost too much. August 15 is one such date—a day when different corners of the world have celebrated liberation, witnessed the closing chapter of war, gathered in fields to sing for peace, and observed ancient traditions of faith. It is the anniversary of India’s independence from Britain in 1947, the opening day of the legendary Woodstock music festival in 1969, the moment the Japanese emperor announced surrender in World War II, and the centuries-old feast of the Assumption of Mary in Catholic tradition. Each story could stand alone as history worth remembering; together, they form a strange and beautiful harmony, a reminder that the human experience is as vast as it is intertwined.

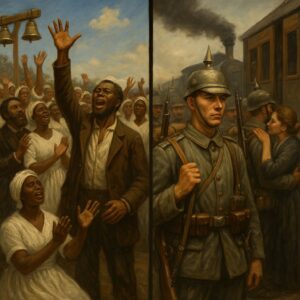

The first chord in this symphony of August 15 was struck in 1947, when India awoke to independence after nearly two centuries under British colonial rule. The midnight before, Jawaharlal Nehru, the new Prime Minister, stood before the Constituent Assembly in New Delhi and declared, “At the stroke of the midnight hour, when the world sleeps, India will awake to life and freedom.” The words were poetic but the moment was real, electric in its intensity. Across the subcontinent, people celebrated in streets draped with tricolor flags, bands played patriotic songs, and prayers were offered in temples, mosques, churches, and gurdwaras.

But freedom came with a terrible price. The British withdrawal also brought Partition—dividing the land into India and the new nation of Pakistan. The hurried drawing of borders triggered one of the largest mass migrations in human history, as millions of Hindus, Muslims, and Sikhs crossed into what they hoped would be safer territory. Violence erupted along the routes, claiming hundreds of thousands of lives. It was a bittersweet birth—an event that embodied both the fulfillment of a dream and the trauma of separation. For India, August 15 would always be a day of pride, but also a reminder of the human cost of freedom.

Two years earlier, another monumental moment had unfolded on August 15—this one resonating across the globe. It was the day Emperor Hirohito’s voice was heard on the radio for the first time by the Japanese people, announcing Japan’s surrender in World War II. The recording, known as the Jewel Voice Broadcast, was delivered in formal, archaic Japanese, making it hard for many listeners to immediately understand. But the meaning was unmistakable: the war was over. After the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Soviet Union’s entry into the war against Japan, the empire’s leaders had concluded that continuing the fight would only bring “ultimate collapse and obliteration of the Japanese nation.”

The announcement marked the end of six years of global conflict, but the day was not one of simple relief. In Tokyo, some wept openly; others bowed their heads in silent grief for the fallen. Across Asia and the Pacific, occupied nations celebrated their liberation. In Allied countries, victory was tempered by mourning for the millions lost. It was a day when the world seemed to exhale, unsure what the next breath would bring in a world reshaped by destruction and diplomacy.

Jump ahead to August 15, 1969, and the world saw a very different gathering—a sprawling, mud-soaked field in Bethel, New York, filled with hundreds of thousands of young people who came for three days of music, peace, and a chance to live, if only briefly, in a vision of harmony. Woodstock was born in the height of the counterculture movement, a time of political protest, generational change, and deep skepticism about authority, fueled in part by the Vietnam War.

The first day opened with folk artist Richie Havens, whose improvised song “Freedom” became an instant anthem. The crowd—eventually numbering close to half a million—was larger than anyone had anticipated, overwhelming the local infrastructure. But despite the chaos, food shortages, and rainstorms that turned the pastures into rivers of mud, the festival remained remarkably peaceful. Strangers shared blankets and meals, strangers danced together to Joan Baez, Santana, and The Grateful Dead. By the time Jimi Hendrix closed the festival with his haunting rendition of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Woodstock had become more than a concert—it was a cultural touchstone, a symbol of what people could create together when they imagined a world built on love rather than division.

And woven into all of this is a thread that stretches far deeper into the past: August 15 is also the Feast of the Assumption of Mary, one of the most important holy days in the Catholic calendar. It commemorates the belief that the Virgin Mary, at the end of her earthly life, was taken up into heaven, body and soul. For centuries, this feast has been marked by processions, masses, and pilgrimages. In villages across Europe, the day is celebrated with flowers, music, and offerings. In some places, it is tied to harvest traditions, giving thanks for the fruits of the earth as well as the hope of eternal life.

In this context, August 15 becomes a date that unites the temporal and the spiritual, the political and the personal. It is about independence on a national scale and on a human scale—freedom from colonial rule, freedom from war, freedom to gather in peace, freedom to believe.

When we look at these events side by side, patterns emerge. India’s independence, Japan’s surrender, Woodstock’s opening, and the Feast of the Assumption all speak to transitions—endings and beginnings, the closing of one chapter and the start of another. They all involve large groups of people coming together, whether in celebration, mourning, or worship. They all are rooted in the human yearning for dignity and meaning.

In 1947, Indians claimed the right to govern themselves. In 1945, Japan acknowledged the need to lay down arms and rebuild. In 1969, a generation sought to redefine community through music and shared experience. And for centuries, believers have looked to the Assumption as a reminder of hope beyond earthly struggles. Each is a different answer to the same question: how do we move forward from where we are now?

August 15, then, is not just a date. It is a chorus sung in many languages and to many tunes, each verse telling a story of struggle and resilience. It is the midnight hour in Delhi, the static-filled voice of an emperor, the electric hum of amplifiers over a muddy field, and the ringing of church bells. It is the waving of flags, the clasping of hands, the lighting of candles. It is, in the truest sense, a day when the world has paused to take stock of what it has endured and what it still hopes to achieve.