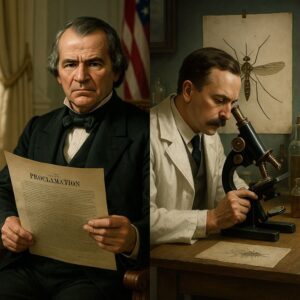

On an August day that might otherwise have passed like any other—humid, slow, the air shimmering above cobblestones—two signatures on two very different pieces of paper nudged the world onto quieter, healthier tracks. On August 20, 1866, President Andrew Johnson proclaimed the last embers of the U.S. Civil War officially extinguished, a legal coda to the most convulsive conflict in American history. Thirty-one years later to the day, on August 20, 1897, a British physician named Ronald Ross peered through a microscope in Secunderabad and found, in the gut of a mosquito, the living chain that bound humankind to one of its oldest scourges. Two acts—one political, one scientific—never met in the same column inches of a newspaper, yet they rhyme: an ending and a beginning, both about the possibility of peace, one between people and the other between people and a parasite.

Consider first the proclamation. By 1866, the cannons had long since fallen silent. Lee had surrendered the previous spring; the armies had stacked their muskets and drifted home, some to farms long neglected, others to cities rethreading their industrial looms. The Union had held, but victory did not feel like triumph. There were ghosts everywhere—empty chairs at rough-hewn tables, burned courthouses along roads that had been turnpikes of death, an unfinished Constitution waiting for amendments that would try to transmute pain into law. Soldiers carried letters creased into soft squares, wedding rings on chains, and injuries that medicine could not name, let alone cure. Reconstruction had begun, but so had an argument about what “reconstruction” meant: restoration or remaking; punishment or pardon; rights on paper or rights in practice.

Johnson’s proclamation of August 20 did not fill this argument with answers. It was a punctuation mark rather than a paragraph—a formal declaration that all the states once in rebellion were at peace, that the “insurrection” was over. Proclamations are a peculiar literary form: they turn facts into law by speaking them out loud. On Johnson’s desk, the document said what history would accept: that the shooting war had ended, that the country could tax and govern as a single thing again, that railways and river ports and courthouses operated under one flag. It did not mend the broken moral timber of the nation; it could not. Paper can only become scaffolding; it is people who must climb it. But the date mattered. Governments tell themselves—and their citizens—where they stand by fixing words to calendars. August 20, 1866 said: this chapter is closed. It did not declare that the next chapter would be easy, or just, or even coherent.

If we listen carefully, we can hear the sounds outside the White House windows that day: hoofbeats, wagon wheels, distant hammers. Peace is noisy at first because rebuilding is noisy. Bricks tumble; saws bite; arguments rise and fall over the price of nails and the length of leases. Freedpeople stood in lines to register their marriages, to sign labor contracts, to find their names written by clerks who didn’t always know how to spell them but were obligated, now, to try. In those rooms, the promise of the Thirteenth Amendment pressed against the reality of Black Codes and vigilante violence. Johnson’s pen could declare peace, but it could not forbid cruelty. The paper ending one war made space, at best, to fight others: the fight for equality, for schooling, for fair wages, for the vote, for dignity. Proclamations can clear the table; they cannot set it.

Shift the lens thirty-one years forward and nine thousand miles east, to a laboratory warm enough that insects hummed like stray wires. There, Ronald Ross hunted a mystery that had stalked humanity since before the first wall was built or the first hymn was sung. Malaria—fever that comes like the tide; chills that shake the bones like a drum; anemia that whitens lips and eyelids; a disease so old that it seems part of the climate—had killed mothers and emperors alike, had shaped road maps and harvest calendars, had whispered into the ears of generals planning campaigns. People blamed night air, marsh mists, the position of stars. Doctors suspected “parasites” but could not complete the story of how. Ross spent long days studying the thin blood of birds and men, and the fragile bodies of insects no wider than a fingernail clipping. On August 20, he held a mosquito under his lens and saw the parasite in its gut: proof that the insect was not incidental but essential, that the mosquito was a bridge carrying the disease from one human island to another.

Where Johnson’s proclamation tried to close a book, Ross’s discovery opened a field. It gave public health what war had taught generals: strategy. Once you know the path of your enemy, you can break it. Drain the swamps. Screen the windows. Hang nets at night like gauzy sanctuaries. Spray the walls. Map the breeding sites the way engineers map rivers. Train nurses to recognize fevers and pharmacists to dispense quinine. Textbooks could now write down what folk wisdom had sensed—stay away from the mosquito—and turn it from caution into program. In a single microscope slide, the world’s view of disease shifted from myth to mechanism, and mechanism is a language that policies can speak.

The beauty of August 20 is therefore not just historical coincidence but conceptual harmony. Ending a civil war and starting a campaign against malaria seem to belong to different shelves of a library; yet both are about weaning the future off chaos. War is a fever that breaks nations; malaria is a war conducted on a cellular front. Johnson’s proclamation, for all its gaps and political controversy, made space for people to imagine a republic bigger than gunfire. Ross’s insight, for all the iterations and refinements that followed, made space for villages to imagine nights quieter than the hungry whine of Anopheles. Each event says: if you trace a problem to its structure—whether constitutional or biological—you have more than hope; you have handles.

This is not to polish away the rough edges. Johnson’s postwar policies are a tangle of pardons and vetoes, leniencies that emboldened former Confederates, and conflicts with a Congress determined to protect the rights of newly freed citizens. Reconstruction was brutally contested; its retreat scarred generations. The proclamation of August 20 stamped a seal on peace while vigilantes were already stitching masks and lawmakers were already imagining barriers at ballot boxes. We must hold both facts: the importance of the statement and the insufficiency of the settlement. The war’s end date is a legal truth; the work of justice is a longer arc, sometimes bent backwards by hands unwilling to learn.

Ross’s discovery, too, did not settle everything. The parasite’s life cycle unfolds with a trickster’s flair—moving from mosquito to human blood to human liver and back to blood again—so the new knowledge was a doorway, not a destination. Eradication would prove to be a greater dream than control. Quinine mitigated but did not cure; newer drugs emerged, the parasite evolved, insecticides worked until they didn’t; climate and poverty colluded to keep breeding grounds where roofs needed nets and nets sometimes went unused because heat and habit trumped instruction. Public health is politics by other means: budgets, logistics, trust. And mosquitoes do not require passports; borders do not hold back wings.

Yet hold the two Augusts in your palm and they warm like twin coins. Both declare that naming a thing matters. Johnson named the end of formal rebellion so that courts and counties could coordinate life after carnage. Ross named the vector so that villages and hospitals could coordinate life after ignorance. We are so used to thinking of power as either a president’s pen or a scientist’s pipette that we forget how they complement each other. Law makes the lanes; science paves them. Without the proclamation, Reconstruction’s bureaucracies would have lacked an anchor; without Ross’s diagrams, public health would have lacked a map. Together they remind us that progress is multidisciplinary: paper and glass, signatures and slides.

Think about the human beings around these events, the ones who didn’t get recorded. In 1866, a widow in Tennessee may have read the proclamation in a newspaper and felt a strange mixture of relief and resentment, hope and hunger. A freedman in South Carolina may have folded the page into his pocket and walked to a meeting where someone explained a contract clause that he didn’t like but might accept for now. A child in Richmond asked her father if the soldiers were really gone this time. Meanwhile, in 1897 India, a soldier shivered in a barracks bed beneath a net that smelled faintly of smoke, a nurse refilled a kerosene lamp, and somewhere a clerk wrote down the number of men feverish in a company that week. History is a telescope, but it is also a field guide—what matters is how it helps the next person act.

Perhaps the most powerful shared lesson of August 20 is that “official” does not mean “finished,” and “discovery” does not mean “delivered.” Those are invitations, not finales. Proclamations summon citizens to build the peace their leaders announce. Discoveries summon communities to adopt the prevention their scientists design. The arc from Johnson to Ross, from political settlement to microbial understanding, is an arc of responsibility migrating outward from the page to the street. The test of any peace is not the date you inscribe but the schools you open, the courts you staff, the farms you replant, the punishments you do not inflict. The test of any discovery is not the journal in which it appears but the clinics you equip, the water you drain, the screens you hang, the lives you lengthen.

We live with their legacies, not as museum pieces but as daily habits. Every election held in a courthouse rebuilt during Reconstruction is a descendant of August 20, 1866. Every night a child sleeps without fever behind a net in a village with a sprayed wall is a descendant of August 20, 1897. And every time disease surges where trust thins, every time resentment is fanned into retrenched inequality, we glimpse where those legacies were neglected. The day’s lessons are not sentimental but stern: peace must be policed by justice; science must be coupled to services.

If you need one image to carry forward, imagine two hands. In the left, a pen above a proclamation; in the right, a hand turning the knurled focusing wheel of a microscope. Between them floats a single imperative: name what is wrong, and then build what will make it right. For all the complexities of Reconstruction, for all the complexities of malaria control, the core is simplicity itself—complex problems demand both authority and understanding, both policy and proof. We honor August 20 by refusing to separate them.

Our century has inherited new plagues and revived old hatreds; we should know by now that emergencies do not stay politely in their categories. Health emergencies are political; political emergencies have public health consequences. A hurricane knocks out power to clinics; a war births a cholera outbreak in camps; a pandemic rearranges the choreography of voting lines. If Ross and Johnson could sit together on a porch and trade notes, they might each be surprised by the other’s vocabulary—amendments and oocysts are not often heard in the same sentence—but they would recognize the moral: legitimacy matters, and so does evidence. You must settle who we are to each other, and you must learn what is happening in our bodies and our water and our air. Only then do you get the sturdy kinds of peace.

There is a kind of courage in both stories that is easy to overlook. Johnson’s political courage, such as it was, is filtered through a record speckled with failure and conflict; he often refused the courage required to protect the newly freed. Still, to say officially that a war is over is to risk being judged on whether the peace that follows is worthy of the sacrifices that bought it. Ross’s courage was the slow kind, the patience that sits through hour after hour of trial and error. It’s romantic to talk about “eureka moments,” but most discoveries are a long apprenticeship in looking, a craft of enduring tedium and doubt. He had to believe his eyes when they told him something many found implausible, and then he had to persuade others without the brute force of bombs or ballots—only sketches, slides, and calm argument.

If our task is to carry this date forward, the path is clear enough. We can build policies that strengthen the fabric of belonging—schools that teach honest histories; voting systems that invite participation rather than restrict it; courts that administer rights consistently. We can also build the infrastructures of health—labs that monitor, clinics that reach the last village, budgets that anticipate rather than react, campaigns that respect culture as much as they respect data. We can measure success not by the absence of crisis headlines but by the presence of ordinary, life-sustaining routines: mornings without gunfire, nights without fever, summers that feel like seasons instead of sieges.

History does not usually offer such a crisp pairing as August 20. That’s part of why it’s worth pausing over. One day, two declarations: we are done killing each other; we now understand how this disease spreads. Neither promise was fully realized, neither will ever be. But the human project is not perfection; it is improvement. To celebrate this date is to recommit to that project—to the steady work of closing the gap between what the law says and what life feels like, between what the microscope shows and what the clinic can supply. It’s to refuse fatalism in the face of old evils by summoning new tools and fairer rules.

And so, each August 20, let’s read both documents again—the proclamation and the notes from a microscope bench—as if they were addressed to us. The first says, “You may set down your rifles.” The second says, “You must pick up your screens.” Together they say, “Make a world where children inherit fewer reasons to fear the dark.” That is the country, the community, the planet worth building: one in which our debates are loud but not lethal, and our fevers rare, brief, and survivable. The calendar does not cause progress, but it can remind us of the days when we made some.

Here’s the story in plain, human terms. On August 20, 1866, the U.S. government officially said, “The Civil War is over.” People had already stopped shooting, but this put a stamp on it. It meant the country could stitch itself back together—messily, unevenly, with a lot of arguments and pain still to come. That paper didn’t fix everything—far from it—but it gave a starting line for rebuilding.

Exactly thirty-one years later, on August 20, 1897, a doctor named Ronald Ross found proof that malaria spreads through mosquitoes. That single moment at a microscope changed how we fight the disease: use nets, drain standing water, screen the windows, and treat people fast. It didn’t end malaria everywhere, but it turned a mystery into a plan.

Both August 20 moments are about the same idea: you can’t fix what you don’t name. One document named the end of a war so the country could move forward. One discovery named the messenger of a killer disease so communities could protect themselves. They’re reminders that progress takes both leadership and learning—laws and labs, proclamations and proof. And they quietly ask us to keep going: build a fairer peace, and put health within everyone’s reach.