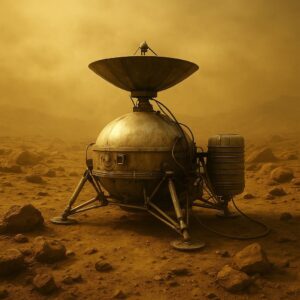

On December 15, 1970, humanity accomplished something that once seemed firmly in the realm of science fiction. A robotic spacecraft built by the Soviet Union survived its descent through the crushing atmosphere of Venus and transmitted data back to Earth from the planet’s surface. That spacecraft was Venera 7, and its success marked one of the boldest and most technically demanding achievements in the history of space exploration. For the first time, a human-made object had landed on another planet and spoken back from the ground itself.

Venus had long taunted scientists with its mystery. From Earth, it appeared serene and luminous, wrapped in thick clouds that reflected sunlight brilliantly. Yet those same clouds hid an environment that was violently hostile. Early radar observations hinted at extreme heat and pressure, but the true nature of Venus remained uncertain throughout much of the 20th century. Sending a spacecraft there was not merely difficult—it bordered on reckless. And yet, that challenge was precisely what drew the attention of Soviet engineers and scientists.

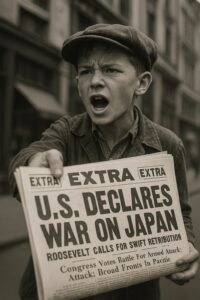

The Soviet Union began conceptualizing missions to Venus in the early 1960s, driven by both scientific ambition and geopolitical rivalry. Space exploration had become a defining arena of the Cold War, and each new milestone carried symbolic weight. But Venus presented a problem that neither ideology nor ambition alone could solve. The planet’s atmosphere was dense enough to crush steel, and its temperatures could melt lead. Any spacecraft sent there would need to survive conditions far beyond anything previously encountered.

Early Venera missions were plagued by failure. Some spacecraft lost communication before reaching Venus. Others succumbed to the planet’s atmosphere during descent. Each failure, however, yielded invaluable data. Engineers learned how electronics behaved under intense heat, how pressure affected structural integrity, and how communication signals degraded under extreme atmospheric density. The Venera program became a masterclass in learning from defeat.

By the time Venera 7 was conceived, the Soviet space program had accumulated nearly a decade of hard-earned experience. The mission represented a shift from atmospheric probes to surface exploration, reflecting a growing understanding that Venus’s geology could offer clues about planetary evolution and Earth’s own climate history. But to reach the surface, engineers had to solve problems no one else had ever solved.

Venera 7 was designed with survival as its primary objective. Unlike earlier probes, it was built like a pressure vessel, with thick walls and minimal moving parts. Its most critical feature was its heat shield, constructed from specialized materials capable of withstanding temperatures exceeding 500 degrees Celsius. This shield would bear the brunt of atmospheric friction during descent, protecting the delicate instruments inside.

Launched from the Baikonur Cosmodrome on December 4, 1970, Venera 7 began its journey quietly, without fanfare outside scientific circles. As it cruised through space toward Venus, mission controllers monitored its systems closely. There would be no second chances. Once it entered Venus’s atmosphere, everything depended on the integrity of its design.

When Venera 7 reached Venus, it plunged into an atmosphere unlike any other encountered by a spacecraft. The air was thick with carbon dioxide, laced with sulfuric acid clouds, and compressed to staggering density. Temperatures climbed rapidly as the probe descended, testing the limits of its shielding. Instruments recorded pressure and heat values that confirmed Venus was far more extreme than previously imagined.

At approximately 25 kilometers above the surface, Venera 7’s parachute deployed—but only briefly. Engineers had anticipated that a conventional descent would expose the probe to lethal heat for too long. The parachute was designed to tear away intentionally, allowing the probe to fall faster and reduce exposure time. It was a calculated risk, one that underscored the mission’s boldness.

The final descent was brutal. Venera 7 slammed into the surface of Venus at high speed, its impact knocking the probe onto its side. For a moment, mission control feared total failure. Communication signals were faint, erratic, and barely distinguishable from background noise. But then came confirmation: the probe was alive.

For 23 minutes, Venera 7 transmitted data from the surface of another planet. Those minutes rewrote the history of space exploration. The data confirmed surface temperatures of approximately 467 degrees Celsius and atmospheric pressures more than 90 times that of Earth. Venus was not merely hot—it was an industrial furnace wrapped in crushing air.

Though the probe was not equipped with cameras, its measurements told a vivid story. Venus was a world shaped by intense volcanic activity and runaway greenhouse effects. Its environment bore little resemblance to Earth, despite similar size and composition. The findings forced scientists to rethink assumptions about planetary habitability and climate stability.

The success of Venera 7 sent shockwaves through the global scientific community. For the Soviet Union, it was a moment of immense pride, demonstrating technical mastery in one of the harshest environments imaginable. For planetary science, it was transformative. Venus was no longer an abstract mystery—it was a measurable reality.

Venera 7 also proved that robotic exploration could succeed where human exploration could not. No astronaut could survive Venus’s surface, but machines, carefully designed and ruthlessly simplified, could endure long enough to bring back knowledge. This realization would guide planetary exploration for decades to come.

The mission’s legacy extended far beyond its brief transmission window. Later Venera missions built upon its success, eventually sending probes equipped with cameras that captured haunting images of Venus’s rocky terrain. Each mission pushed technology further, refining heat resistance, pressure tolerance, and communication systems.

Venera 7’s achievement also carried deeper implications for Earth. Venus became a cautionary tale—a planet that may once have been temperate, now transformed into a hellscape by atmospheric imbalance. Its example added urgency to emerging studies of climate change and greenhouse effects, showing how planetary systems could spiral beyond recovery.

The engineers behind Venera 7 worked largely in obscurity, constrained by secrecy and limited resources. Yet their work rivaled—and in some areas surpassed—that of their Western counterparts. They solved problems not with elegance, but with relentless pragmatism, designing systems that favored durability over sophistication.

In hindsight, Venera 7 stands as one of the most underappreciated triumphs of the Space Age. While moon landings captured public imagination, landing on Venus demanded equal courage and ingenuity. It was not glamorous, not televised, and not easily celebrated—but it was revolutionary.

More than half a century later, no spacecraft has surpassed the audacity of Venera 7’s mission profile. Modern probes still struggle with Venus’s environment, and future missions continue to rely on lessons learned by Soviet engineers in the 1960s. The planet remains one of the greatest challenges in planetary science.

Venera 7 proved that humanity could touch even the most inhospitable worlds. It reminded us that exploration is not about comfort or safety, but about extending knowledge beyond the limits of our environment. In landing on Venus, the Soviet Union did not just win a technical race—it expanded the frontier of what was considered possible.