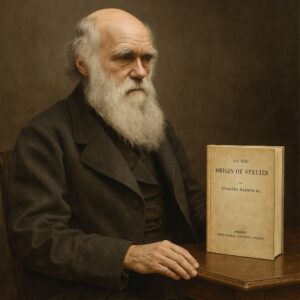

The story of the first Nobel Prizes awarded in Stockholm is not just the tale of a ceremony or the recognition of a few brilliant individuals; it is, at its heart, the story of a world standing at the threshold of a new century and trying to define what progress, virtue, and human achievement truly meant in an age of profound transformation. To appreciate the depth of that moment in 1901, you have to imagine the world as it was—full of contradictions, tensions, breathtaking discoveries, and a rapidly spreading belief that science, literature, and peace could actually reshape the human condition. The ceremony that unfolded on December 10 of that year was the culmination of a man’s extraordinary act of introspection and responsibility, born from a lifetime of invention, wealth, and controversy. That man, of course, was Alfred Nobel. His name today evokes a sense of intellectual honor and global admiration, but in the late 19th century he was most widely known as the inventor of dynamite—a man whose fortune was built from explosives that revolutionized industries but also intensified warfare. The turning point is said to have come when a French newspaper mistakenly published an obituary for him, thinking he had died when it was actually his brother Ludvig. The headline was brutal: “The Merchant of Death is Dead.” Reading how history would remember him shook Nobel deeply. It forced him to confront what kind of legacy he was leaving behind and, more importantly, what kind of legacy he wanted to leave. That moment, whether embellished by retellings or not, sparked his determination to redirect his wealth toward honoring those who “conferred the greatest benefit to humankind,” setting into motion the creation of the Nobel Prizes. By the time he died in 1896, he had left behind a surprise so sweeping that it stunned even his closest family members and advisors. In handwritten instructions, Nobel left the bulk of his fortune—equivalent to well over $300 million in today’s dollars—to establish five annual prizes: Physics, Chemistry, Physiology or Medicine, Literature, and Peace. His will was so unexpected that it caused disputes, legal battles, and years of administrative hurdles before the prizes could finally be awarded. Critics doubted whether such a lofty vision could ever work. Supporters believed it had the power to elevate humanity. Yet despite resistance, the newly formed Nobel Foundation pressed forward, determined to honor Nobel’s wishes and give birth to something the world had never seen before.

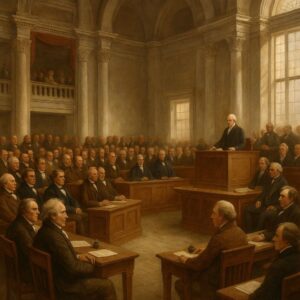

As December 10, 1901 approached—the anniversary of Alfred Nobel’s death chosen as the award date—the city of Stockholm prepared for an event that seemed almost ceremonial in its symbolism: the notion that the new century should begin by celebrating the best minds, the most humane ideals, and the most profound contributions to human progress. Dignitaries from across Europe traveled by train, steamer, and carriage to witness the inaugural ceremony, creating a sense of anticipation that felt like the unveiling of a new era. The first laureates reflected the scientific spirit and humanitarian concerns that had defined the late 19th century. The Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen for his discovery of X-rays—a breakthrough that had stunned the world just six years earlier. Röntgen’s work revealed something previously unimaginable: an invisible force that could pass through flesh and reveal the skeleton beneath. Newspapers had declared it a miracle, doctors embraced it as a revolution in medical diagnosis, and the public saw it as almost supernatural. That his discovery was the first Nobel Prize in Physics felt almost poetic, as if the world were saying that the future would belong to those who revealed the unseen. In Chemistry, the award went to Jacobus Henricus van ’t Hoff, whose groundbreaking work on chemical dynamics and osmotic pressure helped build the foundations of modern physical chemistry. His research explained how chemical reactions understood in everyday life—from food preservation to industrial processes—were governed by universal principles. Meanwhile, in Physiology or Medicine, the prize went to Emil von Behring for his development of serum therapy against diphtheria, a disease that had claimed countless young lives. His antitoxin dramatically reduced childhood mortality and represented one of the era’s greatest medical victories. The award was not merely scientific; for many families across the world, it was profoundly personal. In Literature, the first laureate was the French poet and philosopher Sully Prudhomme, whose works explored justice, introspection, and the emotional dilemmas of modern life. His selection sparked debate—many thought Leo Tolstoy should have been the inaugural laureate—but Prudhomme’s reflective writings resonated with Nobel’s desire to honor idealistic literature. And finally, the Nobel Peace Prize was awarded not in Stockholm but in Christiania (modern-day Oslo), as Nobel had instructed. It went to Henry Dunant, founder of the Red Cross, and Frédéric Passy, a leading advocate for international arbitration. Their selection set an early precedent: that peace was not simply the absence of conflict, but a global undertaking built through compassion, diplomacy, and humanitarian principles.

What made the 1901 ceremony so powerful was not just the prestige or the fame of the recipients but the sense that the world was trying to redefine what mattered. At the dawn of a turbulent century that would soon experience two world wars, technological upheaval, and profound social change, the Nobel Prizes represented a beacon of idealism. They were a statement that even in a world rife with political and industrial ambition, human progress should be measured by enlightenment, empathy, and discovery. Observers who attended the first ceremony described the atmosphere as both solemn and hopeful. Nobel had requested that the awards be given without regard to nationality and without bias—a radical idea in an age still defined by imperial rivalry and rising nationalism. The ceremony, therefore, was not merely a presentation of medals; it was a symbolic gesture toward global unity through intellect and humanitarianism. When Röntgen stepped forward to accept his award, he refused the prize money out of principle, insisting it should be used for scientific research. His humility resonated deeply with the audience, reinforcing the idea that the Nobel Prizes were not just personal honors but milestones for all of humanity. As the laureates were called one by one, people could feel a shift—a recognition that the torch of human progress belonged equally to scientists, writers, doctors, and peacemakers. In the years that followed, the Nobel Prizes became a global institution, one that not only honors brilliance but encourages future generations to push beyond the known boundaries of knowledge and compassion.

The legacy of that first awarding in Stockholm is profound. It laid the foundation for more than a century of scientific breakthroughs, from the structure of DNA to the discovery of pulsars, from life-saving medicines to groundbreaking insights into human rights and international cooperation. The first ceremony created a template for the values the Nobel Prizes would uphold: rigor, integrity, and a belief that great ideas could change the course of humanity. But the deeper story, the one that still resonates today, is that Alfred Nobel turned what could have been a legacy of destruction into one of the most distinguished honors for human upliftment. His choice to invest in the future rather than deny his past remains one of the most extraordinary acts of personal transformation recorded in history. The prizes remind us that human beings can redefine their legacy at any moment, choosing to lift others rather than advance themselves. They remind us that progress is not accidental—it’s built deliberately by those brave enough to question, to create, and to imagine a better world. From the heart of Stockholm in 1901 came a promise: that humanity’s most exceptional minds, no matter their nationality or field, would be recognized not for what they destroyed but for what they built. And more than a century later, that promise still stands, renewed each year on Nobel Day as the world pauses to honor those who continue to expand the boundaries of knowledge, empathy, and peace.