History is full of dates that feel like crossroads, moments where the themes of life, death, and the shifting of generations meet in unexpected ways. August 12 is one such day—a day where the United Nations celebrates International Youth Day, honoring the promise, potential, and resilience of young people around the world. Yet, in a striking counterpoint, it is also a date marked by tragedies from the early 19th century—stories of lost youth, of political turbulence in Britain, of leaders grappling with personal despair and public duty. Together, these threads form a tapestry that reminds us that the human story is one of both hope and heartbreak, often intertwined more closely than we’d like to admit.

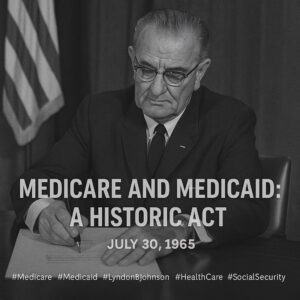

To appreciate the emotional range of August 12, we have to start with the modern celebration. International Youth Day was established by the United Nations in 1999, with the first observance held in 2000. Its purpose is as ambitious as it is necessary: to spotlight the challenges facing young people worldwide, to promote their rights, and to encourage their active participation in shaping a better future. Each year brings a different theme—ranging from employment and civic engagement to environmental sustainability and mental health—because the world young people inherit is as complex as it is full of opportunity.

International Youth Day is not meant to be a single feel-good event. It is, in essence, a global conversation. Governments, NGOs, schools, and youth organizations host conferences, art exhibitions, community projects, and policy dialogues. In cities across the world, young activists stand on stages and speak into microphones, not simply as the leaders of tomorrow but as leaders today. Their voices carry stories of innovation—apps designed to tackle climate change, grassroots campaigns to combat inequality, movements to protect indigenous cultures. On this day, the future doesn’t just seem possible—it feels present and tangible.

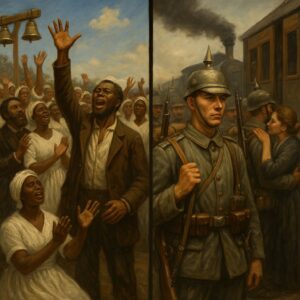

And yet, to fully grasp the poignancy of celebrating youth on August 12, it’s worth reflecting on the other stories the date holds. The early 19th century in Britain was an era of profound political and social upheaval. The Napoleonic Wars had reshaped Europe, the Industrial Revolution was transforming economies and societies, and the British political system was under immense pressure to adapt to these changes. Within this turbulent context, the nation’s leadership faced crises not only in Parliament but also in their personal lives.

One of the tragedies that casts a shadow over August 12 is the untimely death of Robert Stewart, Viscount Castlereagh, Britain’s Foreign Secretary and a key architect of the post-Napoleonic European order. On August 12, 1822, Castlereagh took his own life at the age of 53. His death sent shockwaves through Britain and Europe, for he had been a towering figure in diplomacy, instrumental in shaping the Congress of Vienna in 1815 and in maintaining the delicate balance of power that followed.

Castlereagh’s suicide was not only a personal tragedy but also a political one. He had been under intense strain, dealing with the burden of maintaining peace in a Europe still recovering from decades of war, while also confronting domestic unrest and political opposition. His mental health, likely deteriorating for months if not years, was further pressured by rumors and political attacks. His death opened questions about the human cost of leadership, about how even the most powerful can be crushed under the weight of expectation and responsibility.

The 19th century had its share of youthful promise cut short, too. In an era where life expectancy was shorter and medical knowledge far more limited, many young people—both in public life and out of it—never had the chance to fulfill their potential. The Romantic poets of the time, such as John Keats, Lord Byron, and Percy Bysshe Shelley, embodied this phenomenon. Keats died at 25, Shelley at 29, Byron at 36—youthful deaths that became part of their mythos and, in a way, part of the Romantic ideal itself. Their works brimmed with passion and urgency, perhaps in part because they were written in the shadow of their own mortality.

When we place International Youth Day alongside these earlier losses, the contrast is sharp but illuminating. On one side, we have a modern world actively trying to create conditions in which young people can thrive—celebrating their energy, giving them platforms, seeking to address the structural inequalities that hold them back. On the other, we have a historical period where youth was often cut short by disease, war, or despair, and where even the most accomplished individuals could succumb to isolation and hopelessness.

This juxtaposition prompts reflection on what it means to truly value youth. It’s not just about celebrating birthdays or milestones—it’s about creating environments where young people can flourish, mentally, emotionally, and physically. It’s about recognizing that leaders, too, need support, that even those who seem unshakable can be in need of care. The tragedies of the 19th century remind us that ambition and achievement do not shield anyone from human vulnerability.

The story of Castlereagh in particular resonates in today’s conversations about mental health. In the 1820s, the stigma around mental illness was so great that few spoke of it openly, and effective treatment was virtually nonexistent. Leaders were expected to embody strength without falter, and any sign of weakness could be politically fatal. Castlereagh’s death was reported with a mix of shock and guarded language, reflecting a society uncomfortable with confronting the emotional realities of its heroes.

Today, by contrast, International Youth Day often includes discussions on mental health as a central theme. Young activists talk openly about anxiety, depression, burnout, and the pressures of social media. Organizations promote mental health literacy, advocate for accessible care, and challenge the stigma that still lingers. The message is clear: valuing youth means valuing their well-being, not just their productivity.

The thread connecting these stories—modern and historical—is the idea of potential, both realized and lost. The youth celebrated on August 12 each year are the embodiment of possibility. They are the artists who will shape our culture, the scientists who will push the boundaries of knowledge, the leaders who will inherit a world facing climate change, political division, and technological transformation. But the stories from the 19th century remind us that potential is fragile, that even the brightest flame can be extinguished if we do not protect it.

One could imagine what someone like Castlereagh, with his diplomatic skill and vision, might have contributed had he lived longer in a world more attuned to mental well-being. One could imagine what a Keats or a Shelley might have written had they been given decades more life. And perhaps that imagining is part of the work of International Youth Day—to ensure that today’s young people do not become tomorrow’s lost voices.

In the end, August 12 is a date that bridges centuries, reminding us of the weight of leadership, the fragility of youth, and the responsibility of the present to the future. It is a day to listen—to the joy and ambition in young voices, and to the echoes of those who are gone. It is a day to act—to create policies and communities that nurture potential rather than squander it. And it is a day to remember—that every celebration of life is also an acknowledgment of its precious brevity.