Thanksgiving in America is one of those rare cultural moments that somehow manages to blend history, myth, gratitude, family, food, and national identity into a single day. It arrives each year wrapped in a sense of ritual familiarity—the turkey in the oven, the scent of cinnamon drifting across the house, families gathering around a table, and the soft hum of conversation that feels older than memory itself. But beneath the mashed potatoes, the parades, and the football games lies a deeper, more complicated story—one that reflects the country’s beginnings, its struggles, its changing values, and the way Americans have chosen to define themselves through centuries of transformation. To understand what Thanksgiving truly is, why we celebrate it, and how it came to be, we have to revisit not only the famous feast of 1621, but the broader historical context that shaped it, the myths that grew around it, and the ways generations after reshaped the holiday into a cornerstone of American life.

The story most Americans hear begins with the Pilgrims, that small group of English separatists who crossed the Atlantic in 1620 aboard a cramped vessel called the Mayflower. They landed not at their intended destination in Virginia but on the rocky shores of Cape Cod, battered by weather, malnourished, and utterly unprepared for the brutal New England winter. Nearly half of them did not survive those first months. To understand their plight, imagine stepping onto an unfamiliar continent in December without proper shelter, sufficient food, or the knowledge of how to grow crops in the region’s sandy soil. The Pilgrims weren’t explorers or adventurers—they were religious refugees seeking a place where they could worship freely, yet they found themselves thrust into survival mode. In that moment of desperation, the Wampanoag people, who had lived in the region for thousands of years, made the pivotal decision that would alter the course of American history: they chose to help.

What followed was not the simple, harmonious narrative often told in school textbooks but a complex interaction shaped by diplomacy, mutual need, and the precarious balance of power between indigenous nations experiencing their own period of upheaval. A devastating epidemic had recently swept through parts of the Wampanoag territory, weakening their numbers and altering alliances across the region. Their chief, Massasoit, recognized the strategic advantage of forming an alliance with the struggling newcomers, who could serve as a counterweight against rival groups. It was in this context that a man named Tisquantum—known more widely as Squanto—entered the picture. Having been captured years earlier by English explorers, taken to Europe, and eventually returning to his homeland, he knew both English language and English customs. His experiences positioned him uniquely as a bridge between the two groups. To the Pilgrims, he was a miracle. To the Wampanoag, he was a man with shifting loyalties. To history, he remains a symbol of how survival, cultural exchange, and tragedy intersected in the early days of colonial America.

In the spring of 1621, Squanto taught the Pilgrims techniques that were essential for survival—how to plant corn using fish as fertilizer, how to identify local plants, how to gather resources in a landscape that was still foreign to them. With assistance from the Wampanoag, the Pilgrims’ fortunes began to turn. So when the autumn harvest arrived, marking the first moment of true abundance since their arrival, the Pilgrims decided to hold a celebration of gratitude. Whether they intended for it to be a religious observance, a harvest festival, or a diplomatic gesture remains a point of historical debate. What we do know is that it lasted several days and that the Wampanoag were present—not as invited dinner guests in the modern sense, but as political allies who arrived with warriors and food of their own. The “First Thanksgiving” was less a cozy family dinner and more a communal event blending two cultures whose futures were deeply intertwined yet destined to take very different paths in the years ahead.

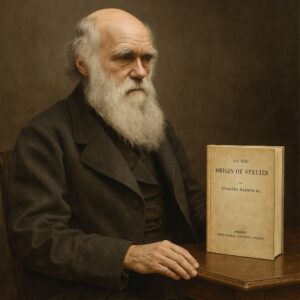

The popular image of the Pilgrims and Wampanoag sharing a peaceful meal, though rooted in fragments of truth, has been shaped significantly by centuries of retelling. In the 19th century, as America faced internal conflict and sought symbols of unity, the story became romanticized. The complexities of colonization, indigenous displacement, and the harsh realities of early American settlement faded into the background, replaced with a more idyllic tableau—one that could be taught to children and embraced as a feel-good origin story. This version played a significant role in the holiday’s evolution. It transformed Thanksgiving from a regional observance—celebrated sporadically in various colonies and states—into a national symbol of gratitude, blessing, and unity.

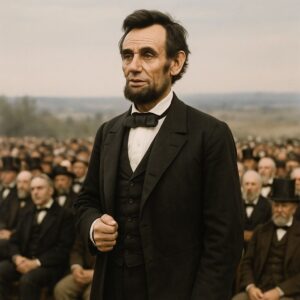

The holiday gained real momentum during the American Civil War, when President Abraham Lincoln sought a way to encourage national healing. In 1863, prompted by the persuasive letters of writer Sarah Josepha Hale (best known for composing “Mary Had a Little Lamb”), Lincoln proclaimed a national day of Thanksgiving. At a time when brothers fought brothers, and the nation seemed at risk of fracturing irreparably, he imagined a holiday where Americans could pause, reflect, and find gratitude in their shared ideals. From that moment forward, Thanksgiving took on a new identity. It wasn’t just about recounting the story of the Pilgrims; it became a holiday rooted in the emotional fabric of the nation—a moment to acknowledge blessings amid hardship and to reaffirm collective resilience.

Throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Thanksgiving absorbed new habits and traditions. Families began gathering around elaborate meals, with turkey emerging as the central dish partly due to its abundance and size—large enough to feed gatherings. Side dishes and desserts reflected local customs and immigrant influences, turning the Thanksgiving table into a celebration of America’s cultural diversity. Parades, later popularized by retailers like Macy’s, introduced a sense of spectacle and excitement. When President Franklin D. Roosevelt shifted the holiday slightly earlier in the calendar during the Great Depression to extend the shopping season, Thanksgiving also cemented its place at the start of the American holiday economy. What began as a harvest celebration became intertwined with commerce, family reunions, national identity, and the rhythm of American life.

Yet Thanksgiving has never been without tension or reflection. For many Native Americans, the holiday is a reminder of the loss, suffering, and cultural destruction that followed European colonization. Some observe it as a national day of mourning, using the occasion to honor ancestors and acknowledge the painful legacy that coexists with the traditional narrative. This duality—celebration and mourning, gratitude and grief—is part of what makes Thanksgiving uniquely American. It forces the country to confront its past even as it celebrates the present.

Still, at its core, Thanksgiving remains centered on the universal human desire to give thanks. Whether someone’s life has been marked by prosperity, hardship, or a mixture of both, the holiday encourages a pause—a moment to gather with people we care about, acknowledge the blessings we have, and reflect on the traditions that brought us here. It reminds us that gratitude doesn’t erase difficulty but can coexist with it, serving as a grounding force in a world that often feels chaotic and uncertain. This spirit of gratitude has allowed Thanksgiving to endure through wars, depressions, pandemics, and dramatic cultural shifts. It has adapted while remaining familiar, evolving while still anchored to its earliest roots.

One of the most powerful aspects of Thanksgiving is how it transcends boundaries. Families of every background, religion, and cultural heritage celebrate it. Immigrant families often adopt it enthusiastically, sometimes incorporating their own dishes into the feast—kimchi next to cranberries, tamales beside stuffing, curries alongside mashed potatoes—turning the table into a reflection of the nation’s rich mosaic. Despite its complicated origins, Thanksgiving has become a shared experience, a moment when millions of people sit down at roughly the same time to eat, talk, laugh, remember, and reconnect. It is perhaps one of the few days when the pace of American life slows down, even if briefly.

The meaning of Thanksgiving continues to evolve in modern society. For some, it is about faith; for others, about family. Some celebrate the abundance of food, while others focus on giving back through volunteer work, donations, or community service. Increasingly, people are also using the day to acknowledge historical truths surrounding Native American experiences and to honor indigenous resilience. In many ways, Thanksgiving has grown into a holiday that balances celebration with reflection—a blend of gratitude, memory, tradition, and awareness.

So what is Thanksgiving? It’s a holiday born from survival and shaped by centuries of storytelling. It is a feast that blends joy with introspection, a tradition that encourages both unity and historical honesty. It is a uniquely American fusion of old and new: the memory of a long-ago harvest festival combined with the modern rituals of food, family gatherings, and collective gratitude. Why do we celebrate it? Because across generations, Americans have found comfort and meaning in setting aside a day to acknowledge the good in their lives, even in difficult times. And how did it come to be? Through a journey that began on the shores of 17th-century New England, passed through the painful contradictions of American history, and ultimately emerged as a national tradition that binds people together each year.

Thanksgiving is not perfect—no holiday with such a complex history could be. But it endures because, at its heart, it speaks to something universal: the desire to pause, to appreciate, to connect, and to remember. That simple act of giving thanks, passed down through centuries, continues to shape the American experience today.